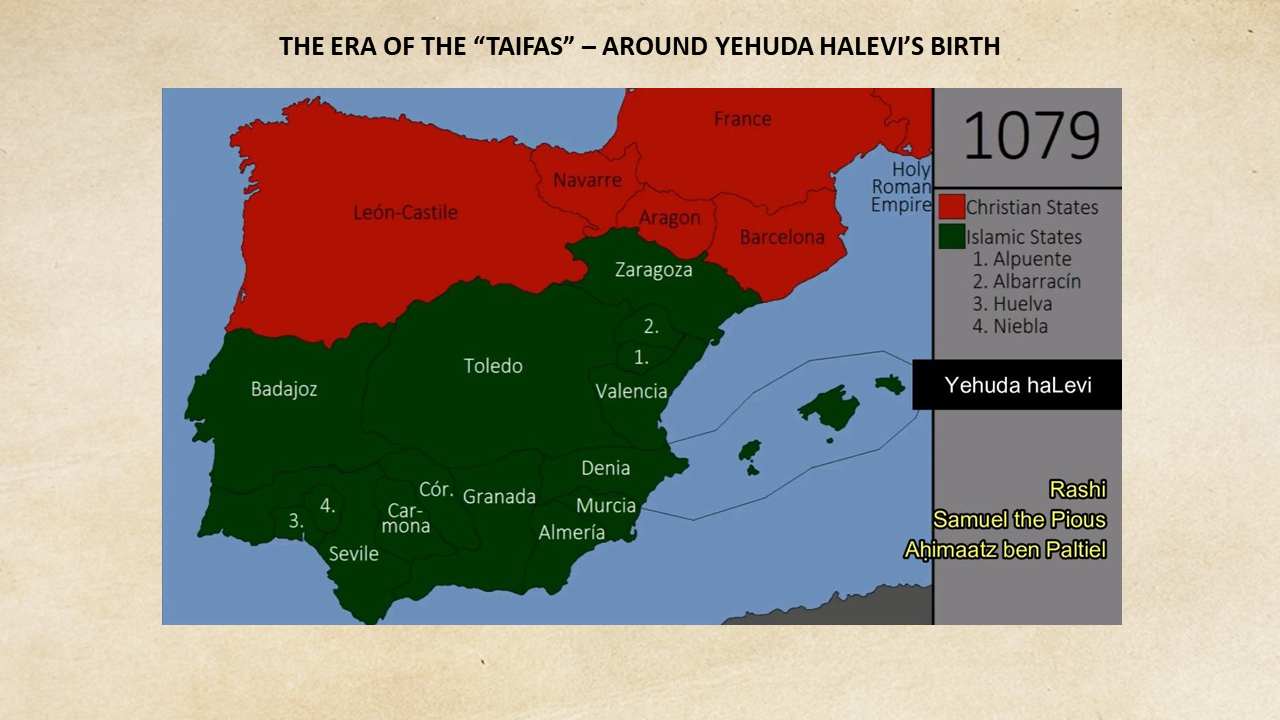

Yehuda haLevi

You can watch Part 1 of this lecture (Yehuda haLevi's Life and Thought) HERE

You can watch Part 2 of this lecture (Yehuda haLevi's Poetry) HERE

You can watch a video on a Muwaššaḥ by Yehuda haLevi HERE

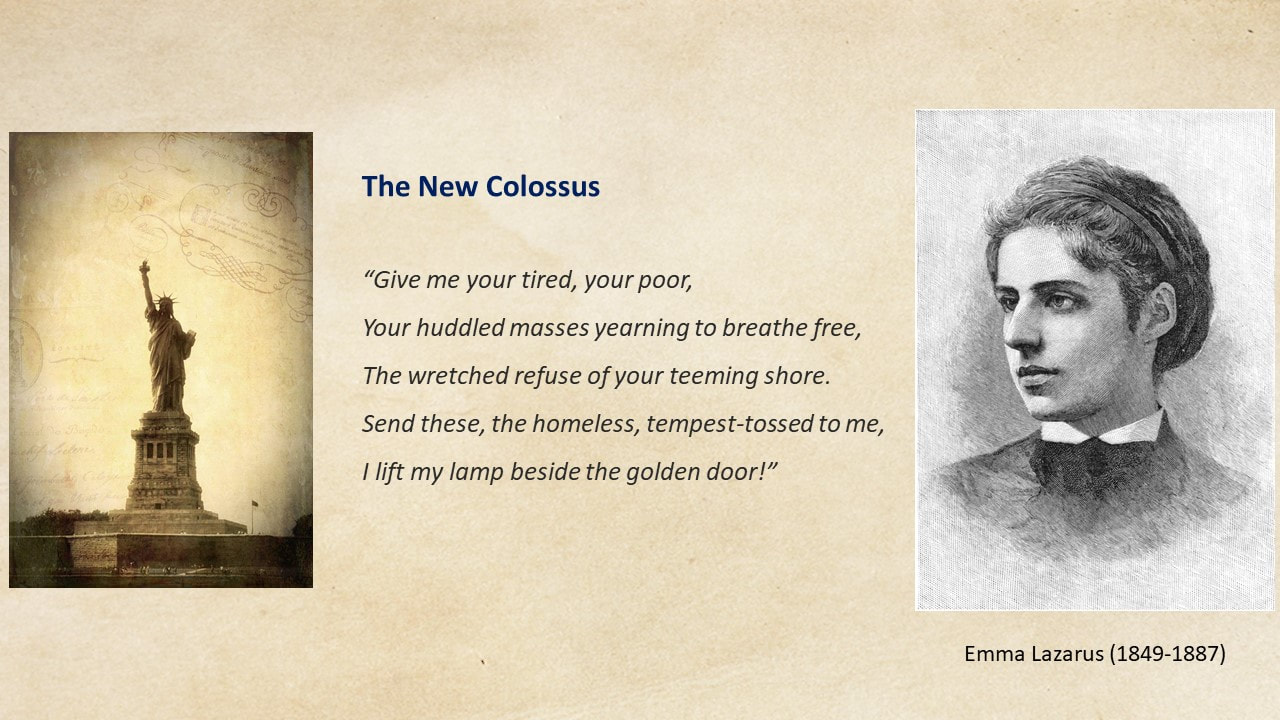

An entirely different translation is by Emma Lazarus (1849-1887).

Emma Lazarus is most known for her poem "The New Colossus"

which she wrote in dedication of the Statue of Liberty.

The poem is inscribed in the Statue's pedestal.

Emma Lazarus is most known for her poem "The New Colossus"

which she wrote in dedication of the Statue of Liberty.

The poem is inscribed in the Statue's pedestal.

Emma Lazarus did not know Hebrew.

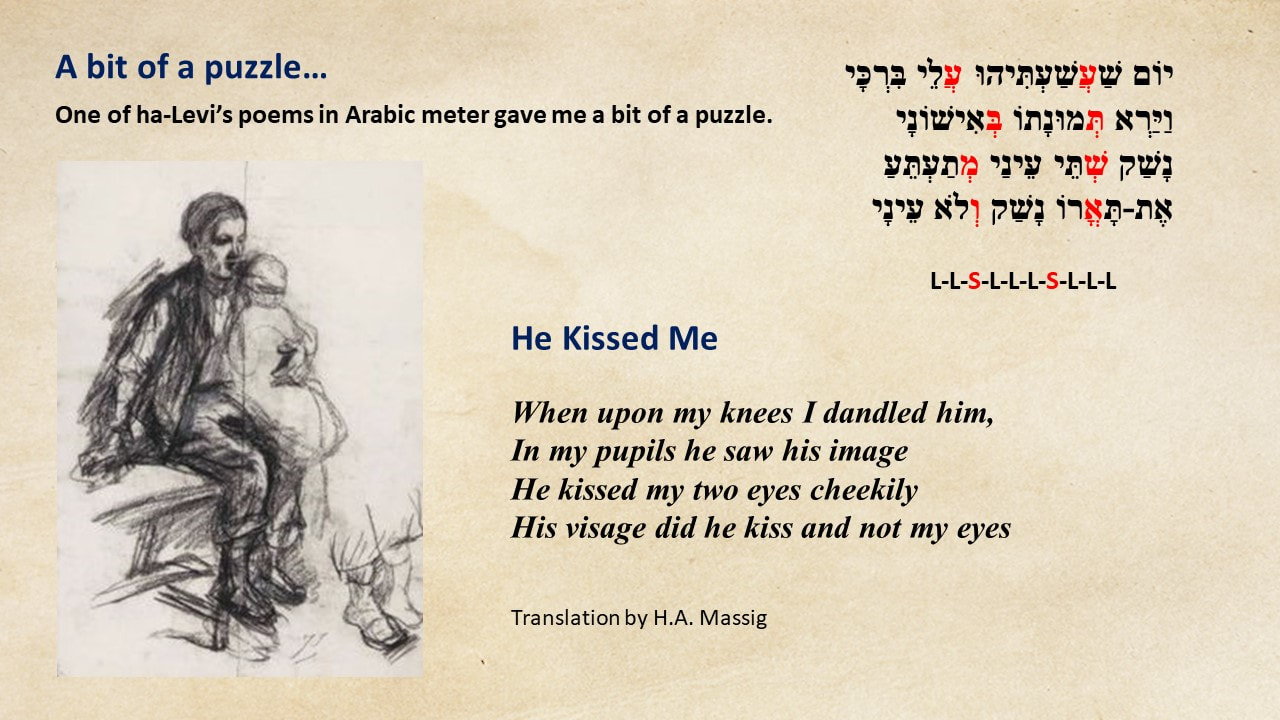

What was her source and why did she interpret the poem

in an homo-erotic way?

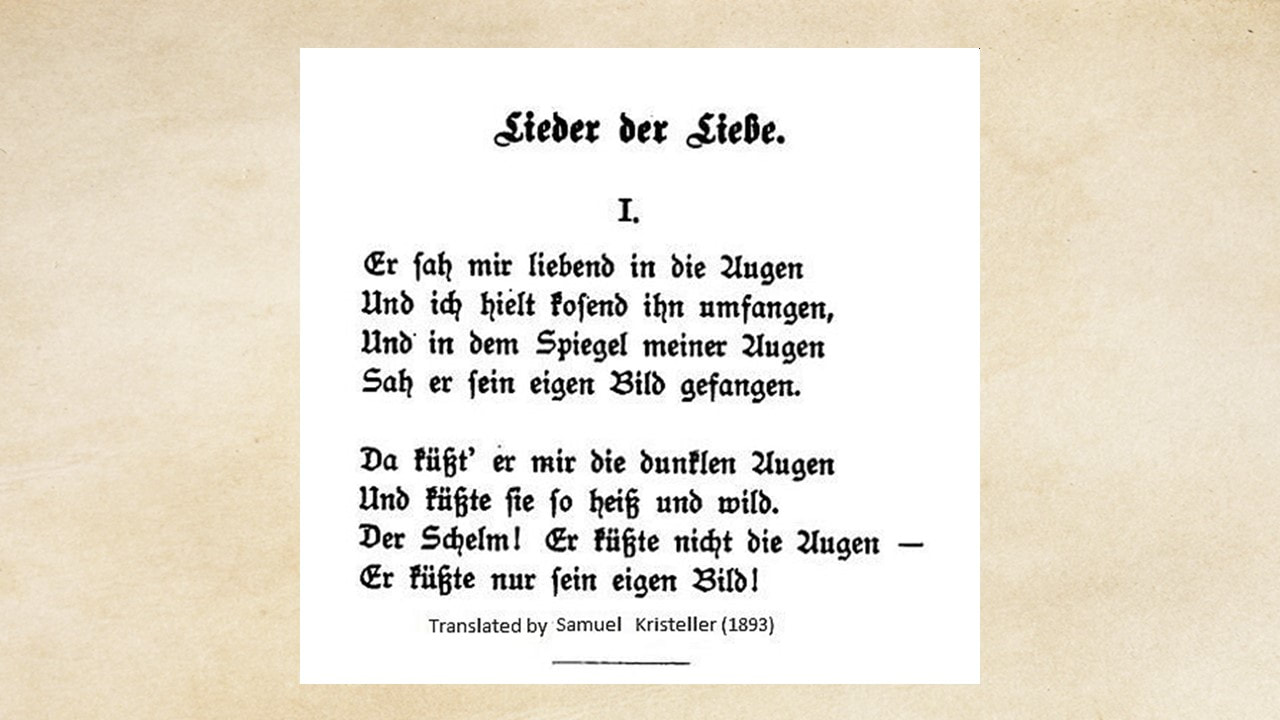

I discovered that her version was based on

a German translation of our poem:

What was her source and why did she interpret the poem

in an homo-erotic way?

I discovered that her version was based on

a German translation of our poem:

The conclusion then has to be that the poem is not about a young child

on his lap, but that instead it has an erotic connotation.

Given the fact that, in the poem, he talks about a male figure,

the conclusion then has to be that this is another example of the

homo-erotic genre that we have seen before (See: Andalusian Poetry).

I then revised my translation as follows:

on his lap, but that instead it has an erotic connotation.

Given the fact that, in the poem, he talks about a male figure,

the conclusion then has to be that this is another example of the

homo-erotic genre that we have seen before (See: Andalusian Poetry).

I then revised my translation as follows:

Whether Yehuda haLevi was indeed involved at some point

in homo-erotic relations, or if he merely wrote this poem

to cover yet another popular genre, remains anyone's guess.

in homo-erotic relations, or if he merely wrote this poem

to cover yet another popular genre, remains anyone's guess.

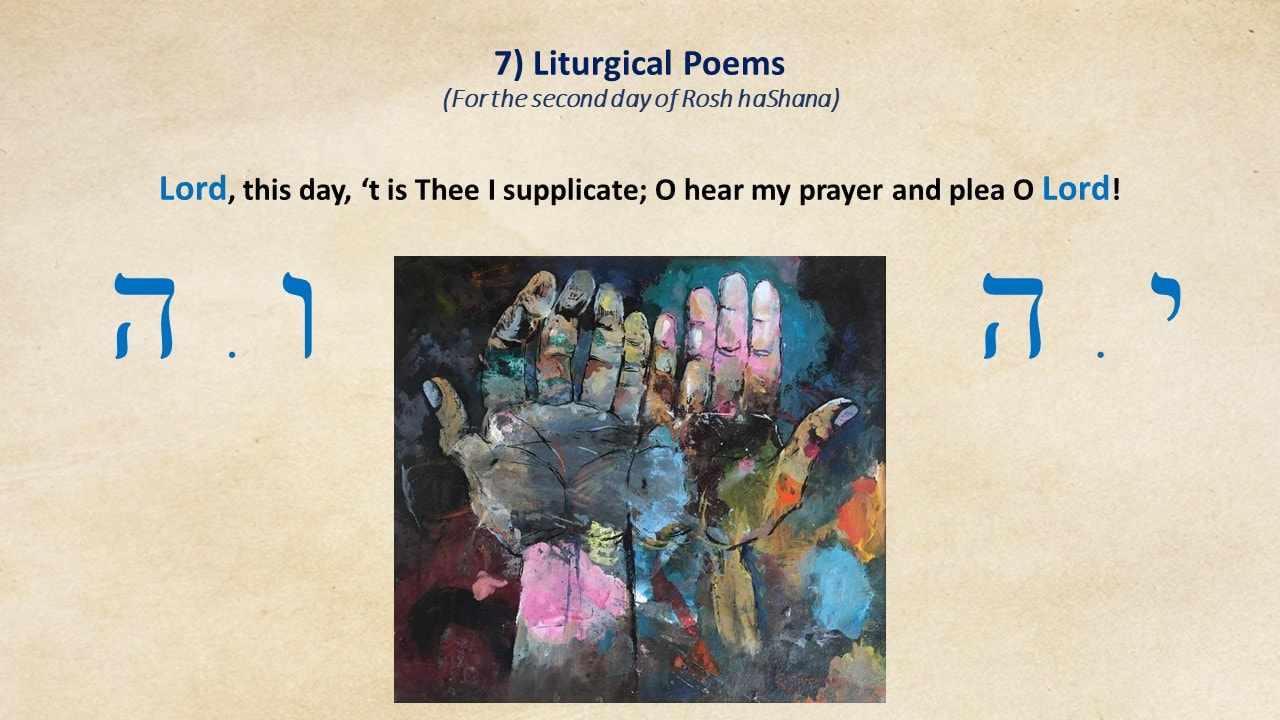

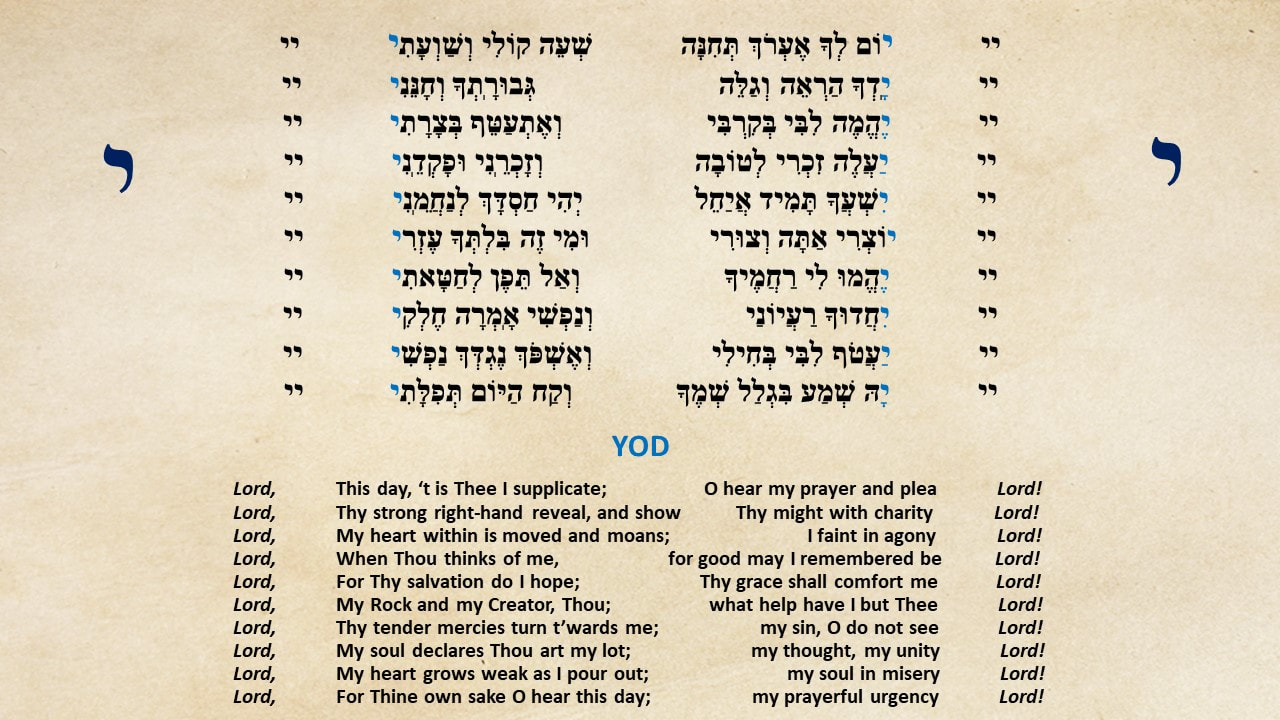

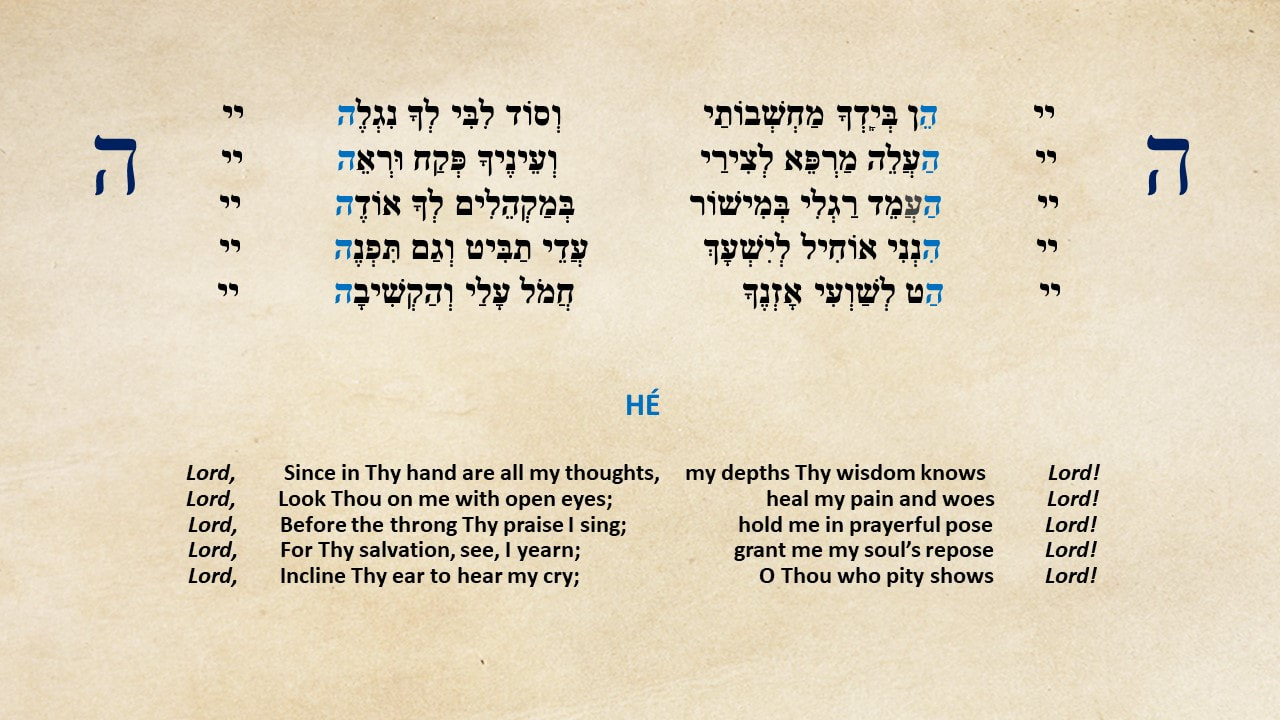

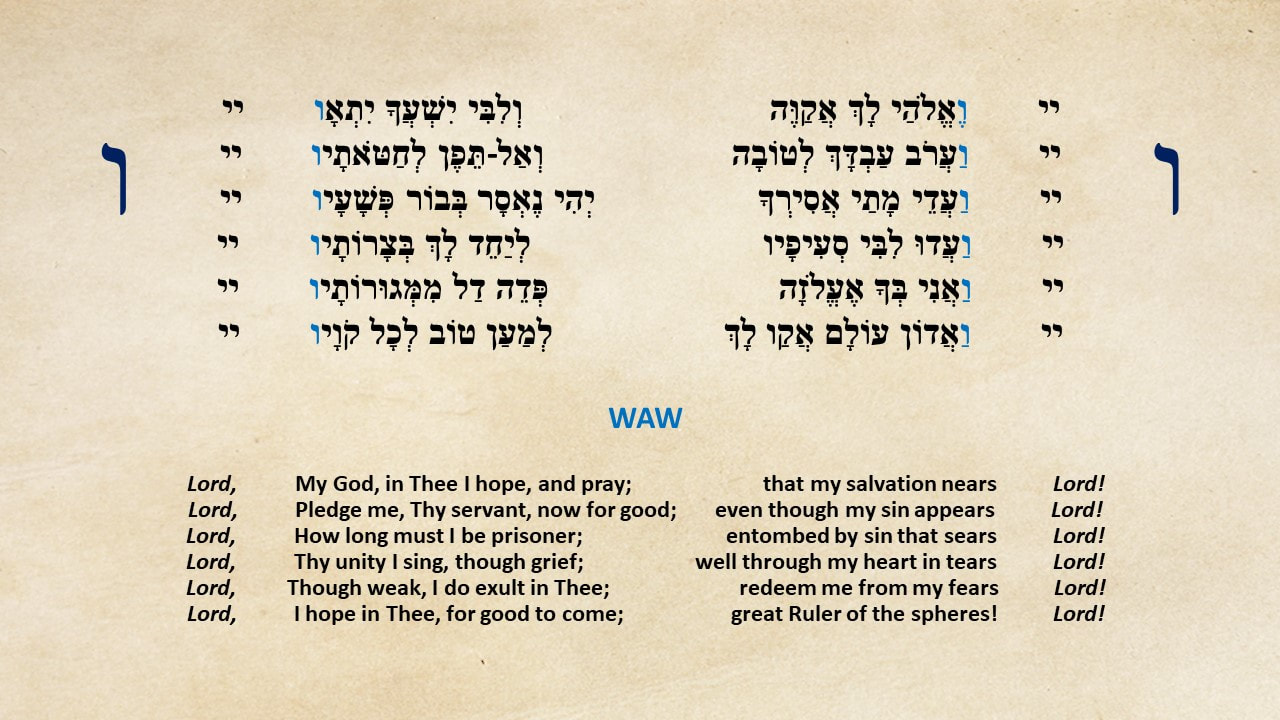

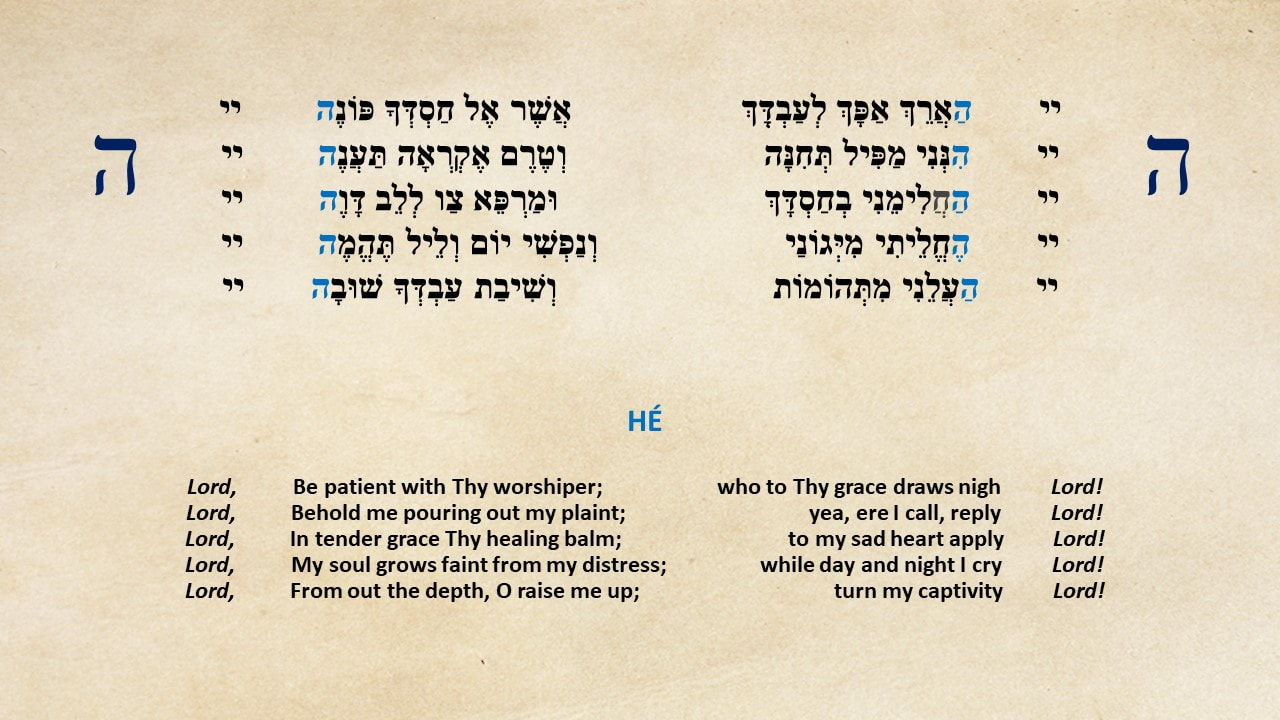

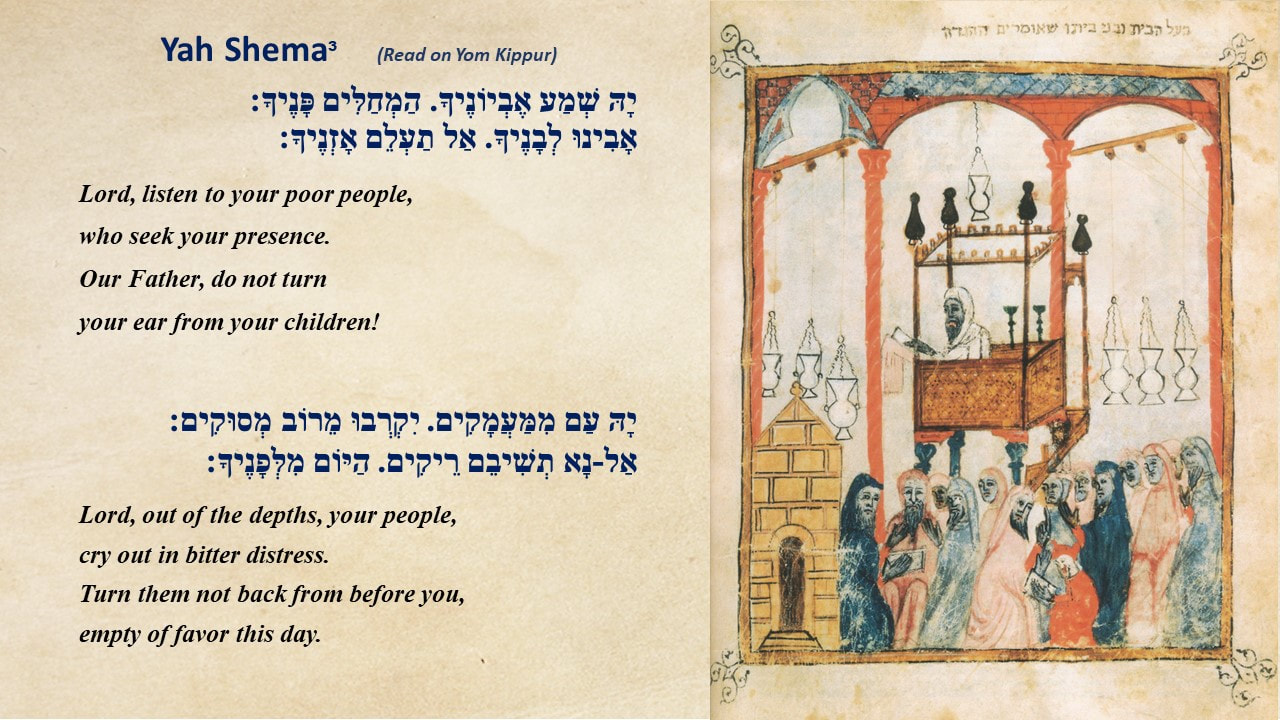

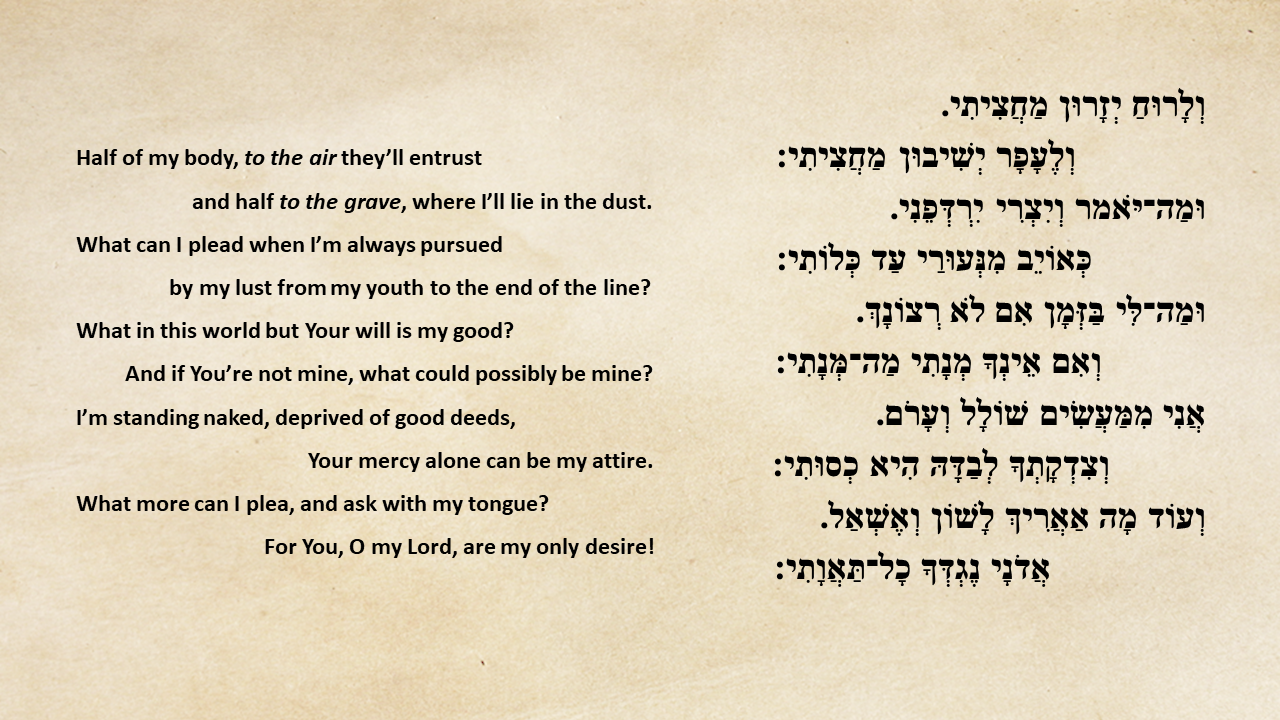

The next poem is built around the "Tetragrammaton"; the Four-Letter-Name of God which, according to Jewish tradition, is never pronounced as such. Instead, ones says "Adonai" (Lord).

The four letters are י (Y, 'yod'), ה (H, 'hey'), ו (W, 'waw'), ה (H, 'hey').

Parallel to the four letters of the divine name, the poem has four strophes. Every line in the poem begins and starts with "Adonai". As far as the line in between these two mentionings of 'Lord', each verse in the first strophe begins and ends with the letter י (Y), each verse in the second strophe with the letter ה (H), each verse in the third with ו (W), and each verse in the fourth and last strophe with ה (H).

On top of these features, Yehuda haLevi builds another 'special effect' in this poem... Hebrew letters also have a numerical value (like Roman letters: I = 1, V = 5, X = 10, etc.) The Hebrew letters Y, H, and Wresemble the numbers 10, 5, 6, and 5. HaLevi has in the first strophe (for Y) ten verses, in the strophe focused around H five verses, in the third strophe built around the W six verses, and in the final strophe again five verses for H.

Here is a recording of Ya Shema in a Medieval,

almost Gregorian style:

"Yah Shema" in a Western-Sephardic melody:

And finally a recording of "Yah Shema" in a Sephardi tune

as used in North Africa and the Middle East:

as used in North Africa and the Middle East:

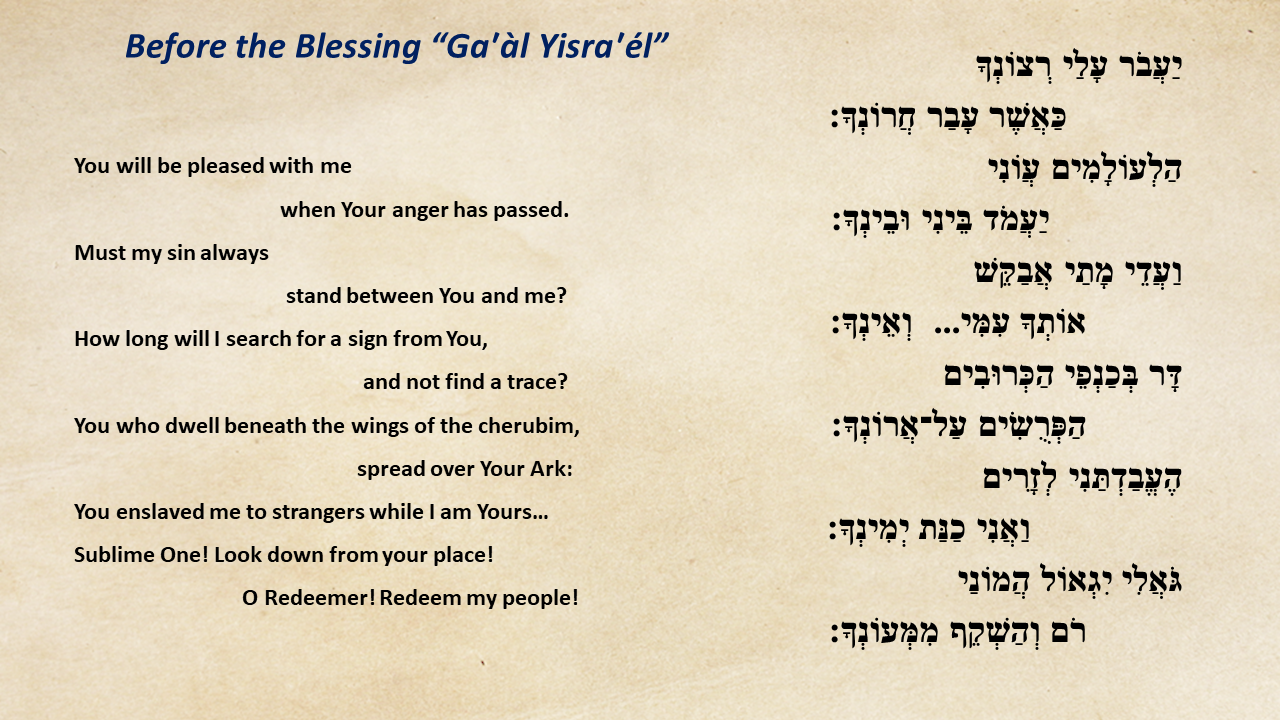

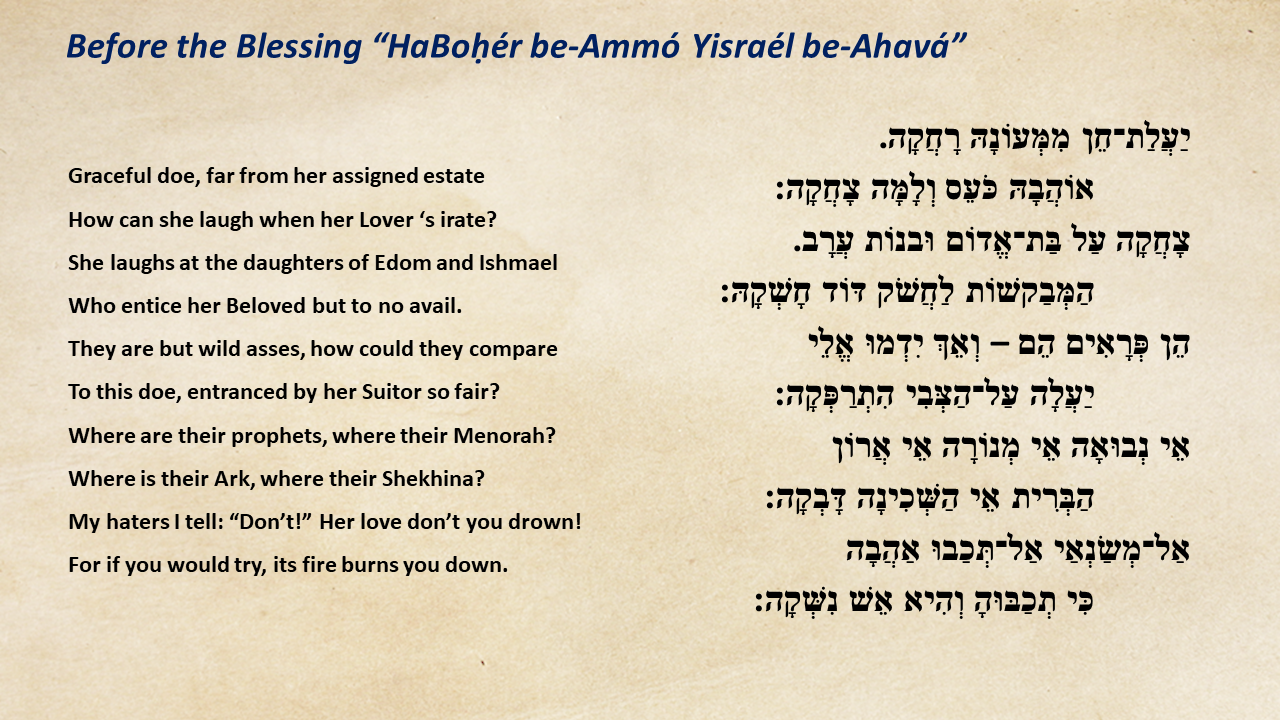

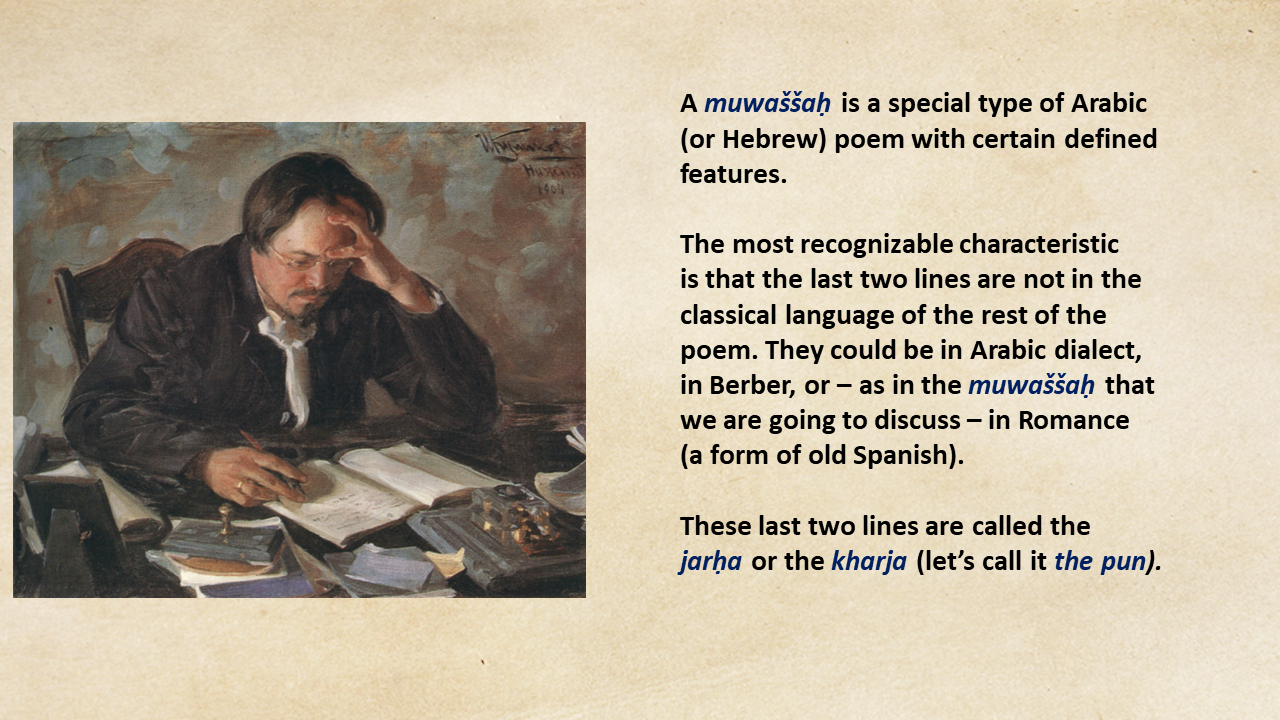

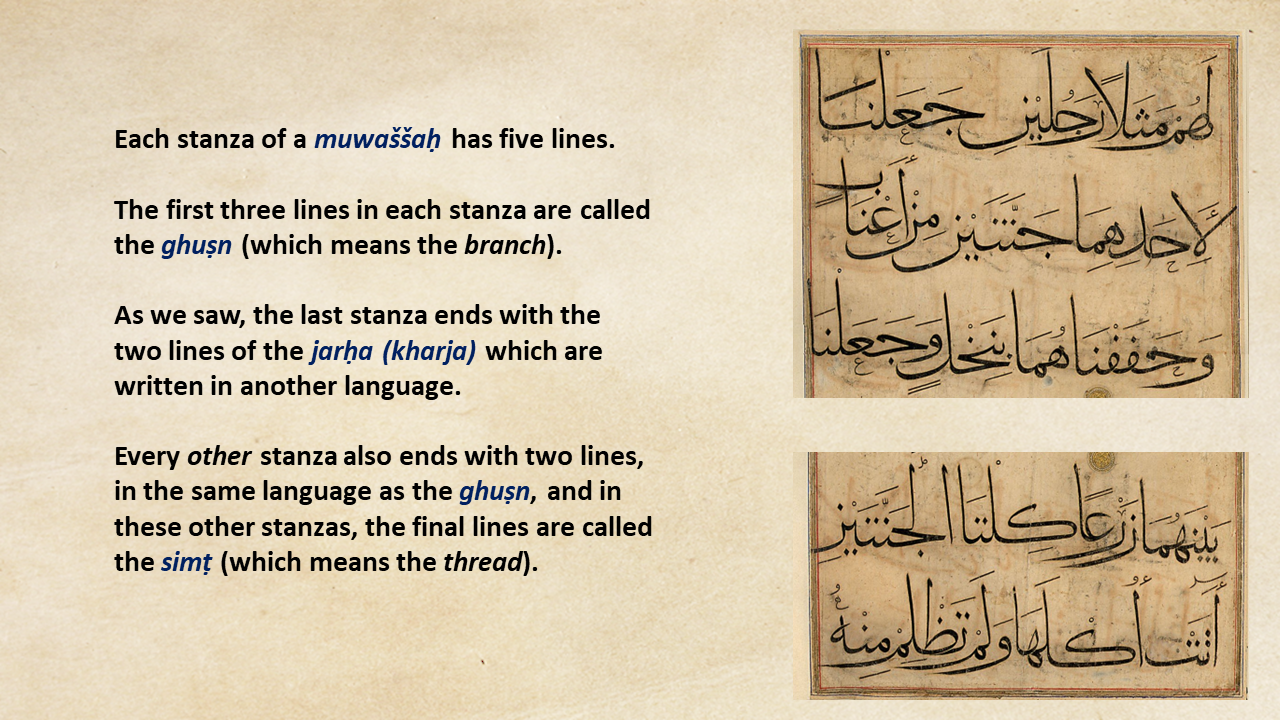

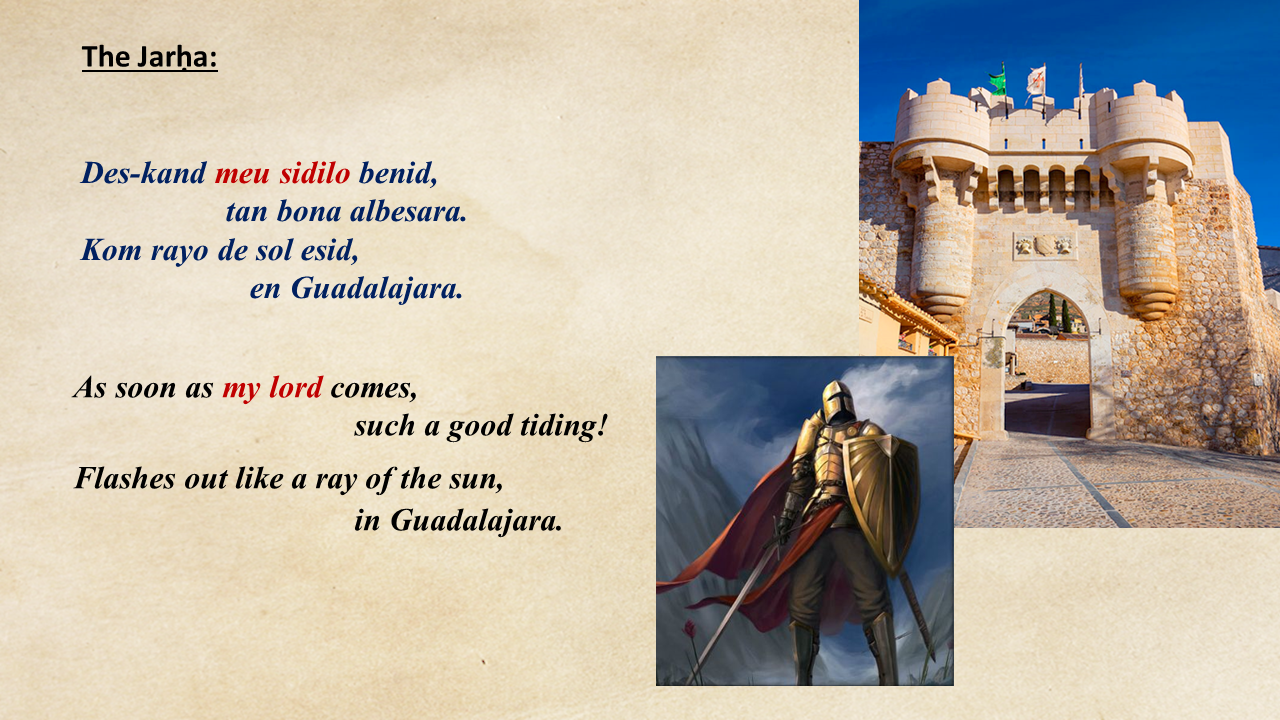

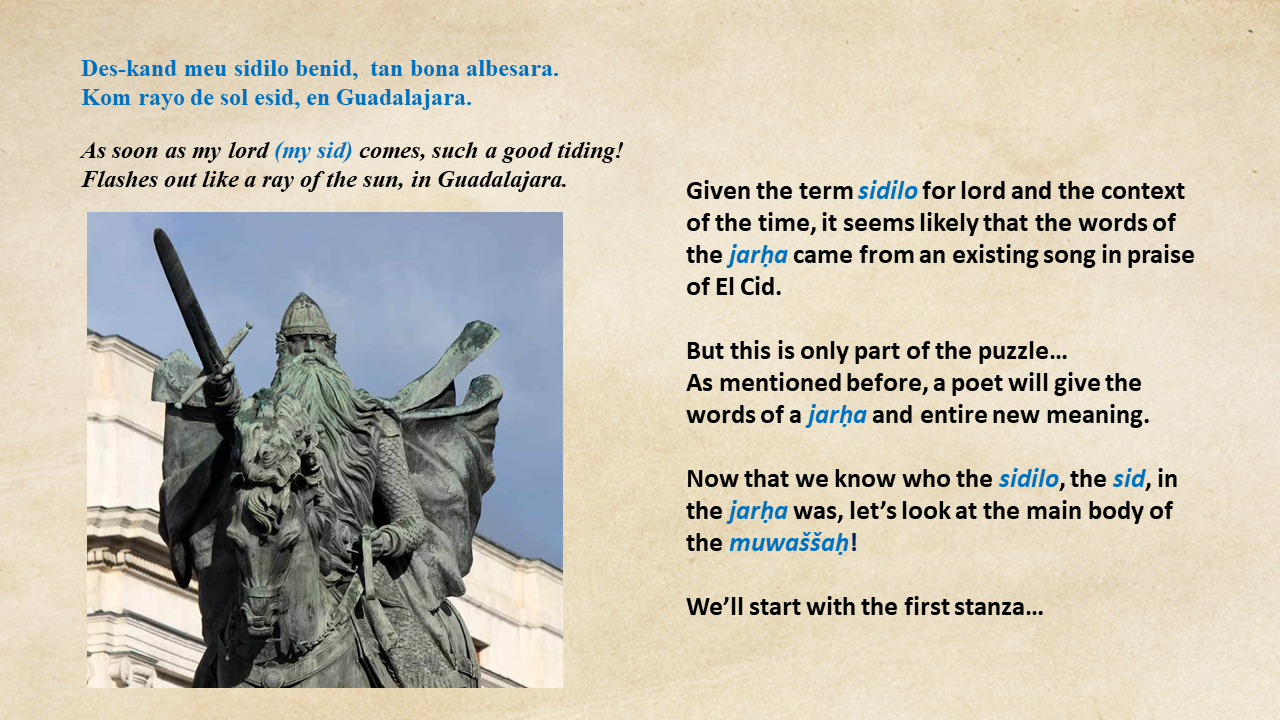

The following poem by Yehuda haLevi is a so-called Muwaššaḥ.

Perhaps the most obvious feature of early Muwaššaḥs is that its last two lines (which are called the djarḥa) are in a different language than the rest of the poem. If the poem is in Hebrew, the djarḥa can be in Arabic,

or Berber, or in Mozarabic (Spanish).

Usually, the djarḥa is an already existing, popular song or poem.

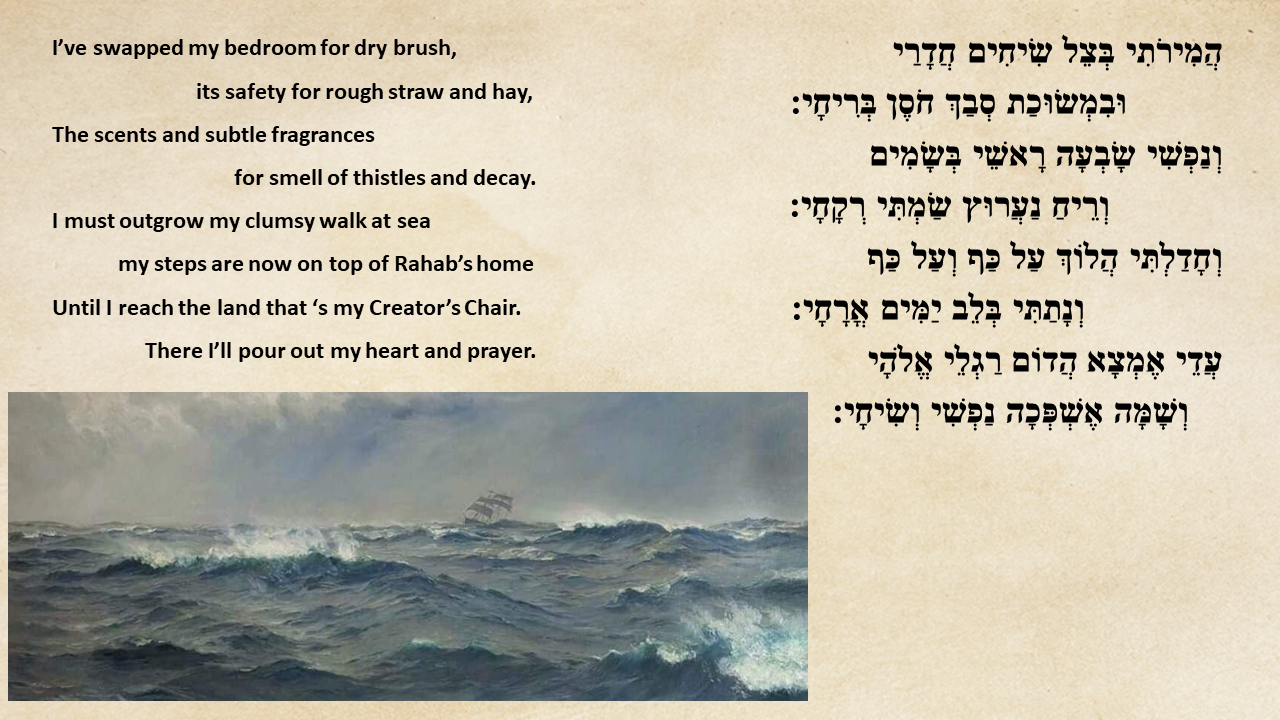

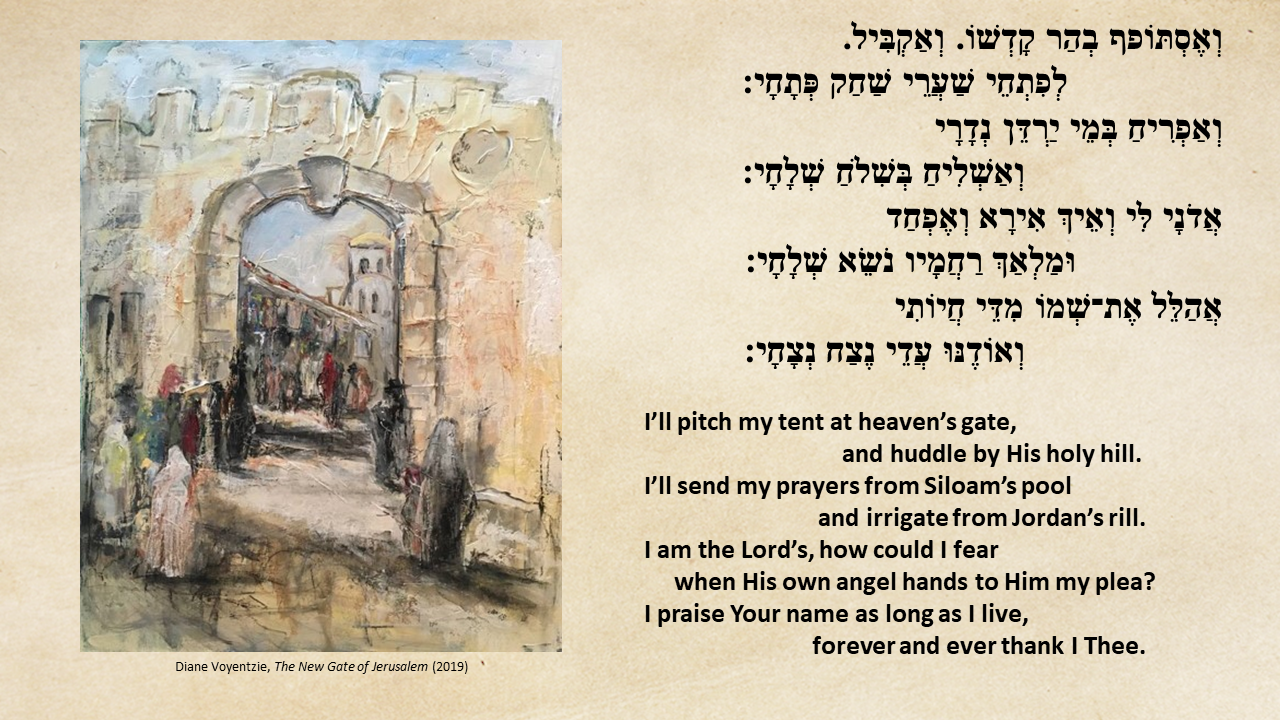

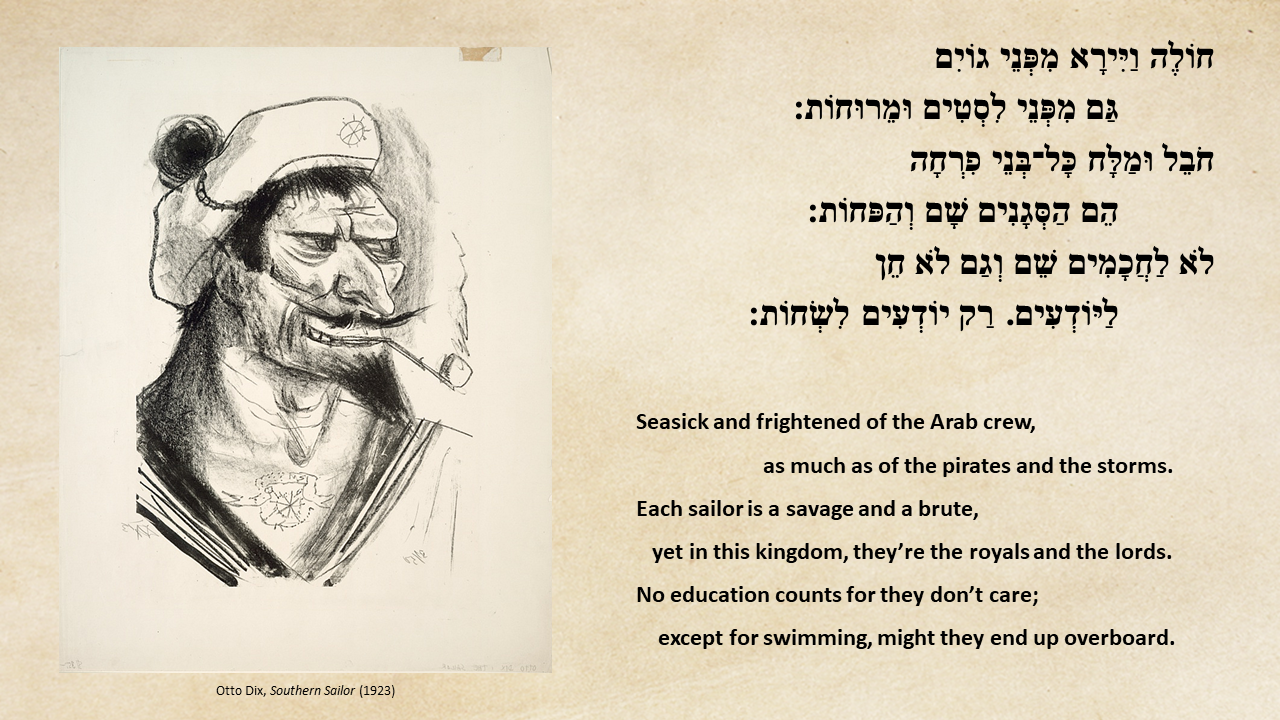

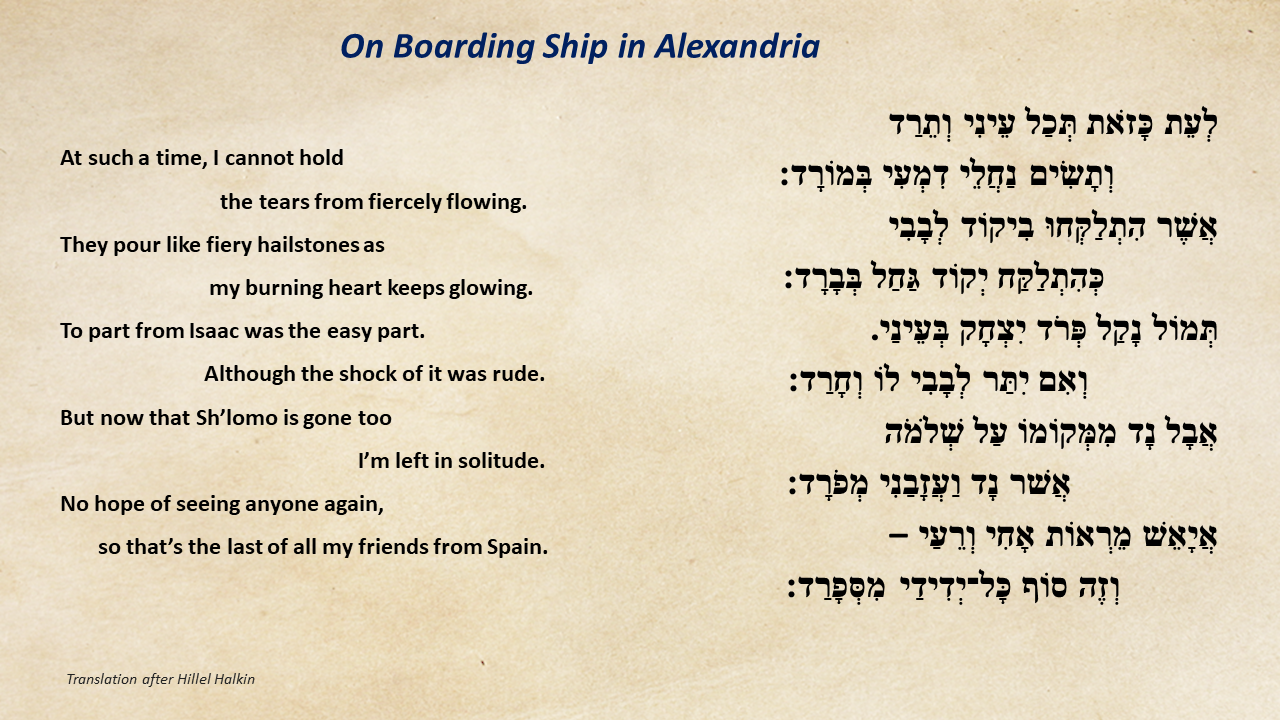

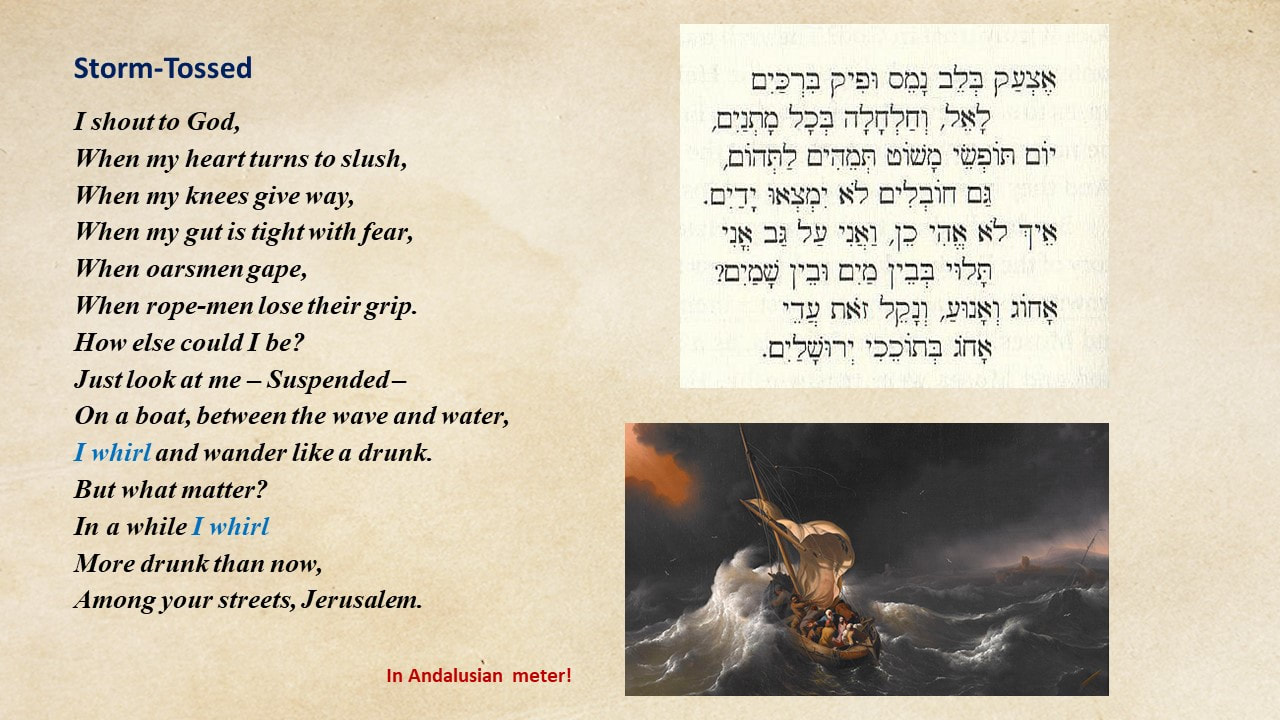

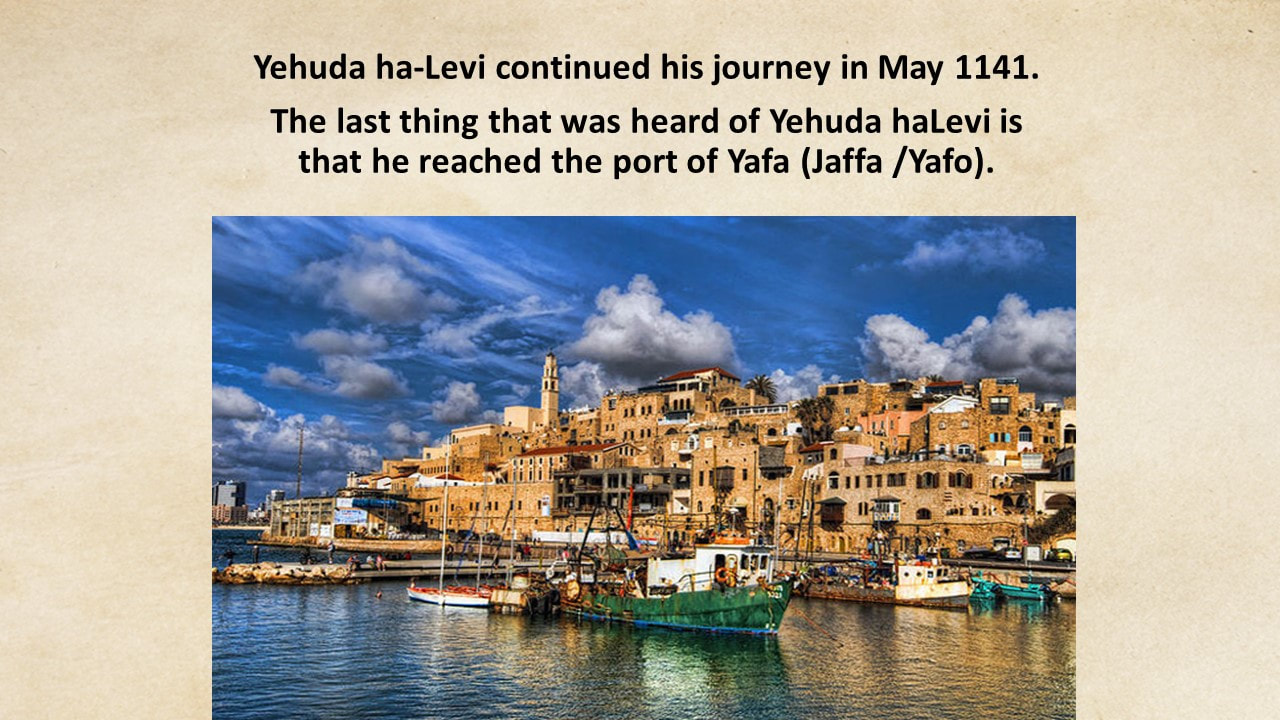

In 1140, Yehuda leaves his possessions and family in Spain behind

and travels to the Holy Land, stopping on the way in Egypt.