Rabbi Sjimon R. den Hollander

A Mikwèh [1] is a collection or gathering of water that fulfills an essential role in the religious life of the Jewish people.

The Background:

According to Torah law (also called the “Law of Moses”) a person can become ritually ‘impure’. This ‘impurity’ does not suggest sinfulness and is most often not perceived as negative in itself. The most important consequence of such impurity was that being impure would (temporarily) disqualify someone from visiting the Temple in Jerusalem. It is generally assumed that the one of the main functions of such a concept was to instill a higher level of awe and respect to the person while entering the Temple and participating in its service. Biblically speaking, there were several levels of ritual impurity, depending on what had brought the impurity about, and related to these levels, there were distinct rituals for removing the impurity. In some cases, for minor levels, the impurity would cease automatically at the end of the day. For others, only the washing of the person’s hands was required. In the most severe case, after touching a corpse, a highly complicated ritual was involved that lasted a week for the impurity to be removed. In many cases however, the appropriate procedure was for a person to totally immerse him or herself in water. Some Laws of Ritual Purity Perpetuated after the Destruction of the Temple:

After the destruction of the Temple, maintaining these practices had become less relevant. Therefore, in most cases, the rabbis of the Talmud decided to temporarily abolish them until the time when, one day in the future, the Temple would be rebuilt. However a number of exceptions were made for cases in which the practice would continue. The ritual washing of hands in certain occasions, such as before eating bread is such an example in which purity laws were perpetuated. Other examples directly involve the topic of our article, the Mikwèh (which is a body of water that fulfills a number of prescribed conditions; more about that later). These examples are: Firstly, the immersion of someone’s entire body at the occasion of his/her conversion to Judaism (which, as a side note, also explains the origin of Christian Baptism). Secondly, the practice to dip newly acquired metal and glass food utensils in such a body of water. And thirdly, the requirement for a menstruant woman to immerse herself after a period of separation from her husband, before she can resume intimate relations. Similarly, such an immersion is required at the end of a period following giving birth. Requirements for a Mikwèh:

Water, like people and many objects can become ritually impure. Under Torah law, however, there are two distinct conditions that make a body of water immune from becoming impure. In other words, under two possible circumstances will water always be pure. According to rabbinic law, exactly such water is needed if one would immerse oneself for the purpose of purification. Only water that is inherently pure can be used for this specific ritual. The first scenario involves rain water that has naturally gathered into a basin. However, the flow of the water into the basin must happen without any interruption, and there is a number of rather complicating additional conditions. One of them is that the rain water cannot flow through any metal pipes or through certain vessels. Also, once the rain water is gathered into the basin, it has to be still, i.e. it has to stop flowing. This does limit certain bodies of water to be used as a Mikwèh. For instance, a flowing river that is primarily fed by rainwater is unfit for ritual immersion. A second scenario involves water that flows uninterruptedly from an active spring. This involves a different set of prerequisites, which are generally less complicated. Most significantly, the water can be used even if it keeps flowing from the spring well. Therefore, if a flowing river is primarily fed by spring water, it can be used for ritual immersion. A Mikwèh in Uganda:

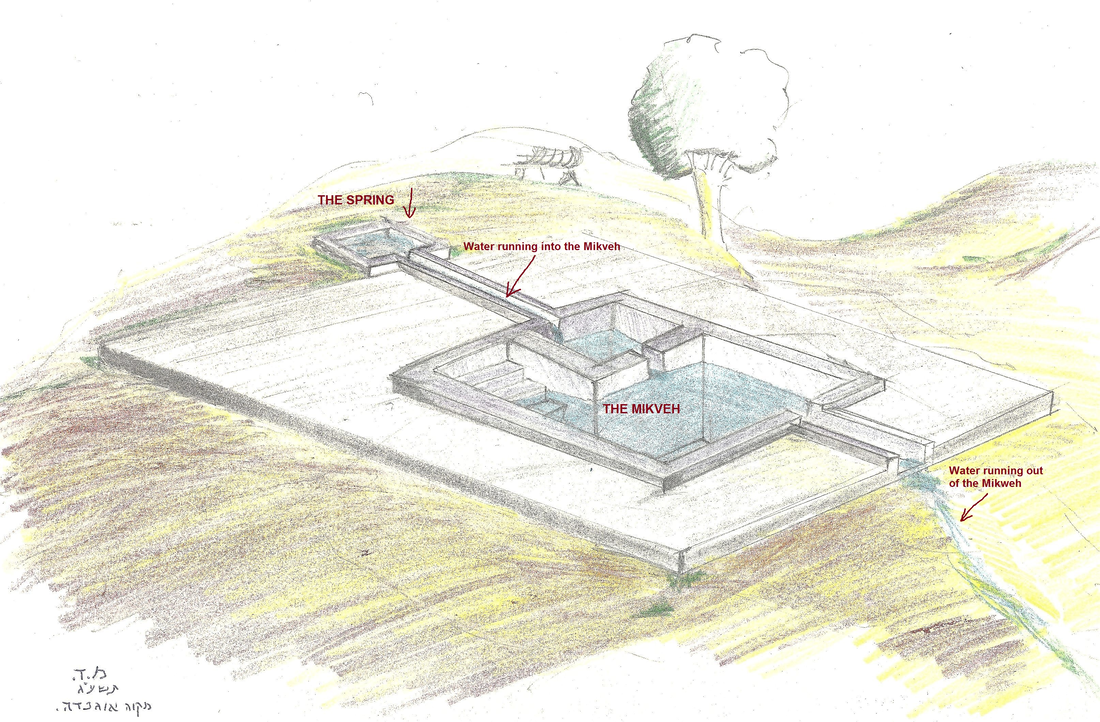

It is this second type of Mikwèh that is used by the Jewish community in the Pallisa district of Uganda. The water flows from the spring into the Mikwèh basin and back out again (see below). In the second illustration below, one can see the actual water spring and a channel leading to the Mikwèh. (Photography: Menachem Kuchar)

The actual Mikwèh is made slightly removed from the spring itself, to create safer conditions for immersion as well as an environment of privacy by means of walled enclosure as the immersion is typically performed without clothing to avoid anything that could prevent the water from toughing every part of the body.

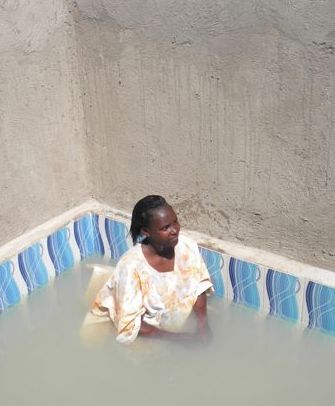

The third illustration shows the actual Mikwèh: (Photography: Menachem Kuchar)

Making use of a spring and flowing water offered the significant advantage that it doesn’t create a breeding ground for mosquitoes. The alternative option for building a Mikwèh, namely with collected still-standing rainwater, would instead have produced a dangerous source of malaria.

In addition, in the way the Mikwèh was built with the water flowing out on the other side, it can now be used to irrigate the crops on the land that feed the people! The Minimal Amount of Water in a Mikwèh:

It seems obvious that a Mikwèh should be sufficiently big to contain enough water to cover the entire body of an average person. According to some authorities, as long as a person’s whole body can be covered with water, then the Mikwèh is sufficient for him/her. Most of the rabbis of the Talmud however held that the quantity of water has to be at least 40 se’ah. The question then immediately comes up: How much is a se’ah? Typically for most things Jewish, that is a matter of debate. It doesn’t really help to know that a se’ah is supposed to be the same size as 144 eggs… How big the average eggs in the time of the Talmud were, is another point of discussion. In short, the opinions on the minimal quantity of water in a “ritual bath” differ from 293.2 liter (77.5 gallons) to a much stricter opinion that quotes a minimal amount of 572 liter (151 gallons). Nowadays, as there is no maximum quantity of water, all Mikwa’ot, are built larger than the biggest quoted minimum, to accommodate all opinions. The above-mentioned immersion of new cooking utensils requires a smaller minimum amount of water but can be done in the same Mikwèh as well. Other Types of Mikwèh: Many of the world’s natural bodies of water, such as seas, oceans, spring-fed lakes, and spring-fed rivers are Mikwa’ot as well and can be used for purification purposes. Before the construction of this Ugandan Mikwèh, the members of the community generally utilized a nearby river, which offered several hazards, such as the presence of parasites, water snakes and other creatures that live in the rivers. When the Mikwèh is Used: According to Jewish practice, immersing in a Mikwèh is required on several occasions. 1. Most importantly, a Jewish woman is required to immerse after a number of days following her menstruation. During this period, she and her husband are not allowed to be together in an intimate way, until she immerses in the Mikwèh or, as we saw before in another valid body of water. Initially, according to Torah law, in most cases this period of semi-separation lasted 7 days in total, starting from the unset of her monthly period. As a result of a development that started in Talmudic times in Babylonia, the custom evolved into a counting of seven days starting from the end of the woman’s menstruation (often resulting in a total of about 12 days on average). This approach has become the general practice of virtually all observant Jewish communities. 2. As the practice of monthly immersion is only observed in the context of marital life, an unmarried woman does not visit the Mikwèh. Therefore, her first visit to the Mikwèh is typically on the night before her wedding. 3. The above described practice is also observed after a woman gives birth. 4. All Jewish converts, both men and women, immerse in a Mikwèh after they have been accepted by a Jewish court (a Beth Din). This immersion constitutes their entering into the Jewish people. 5. In all these occasions, the ritual of immersing oneself in a Mikwèh, is more than just a ritualistic or legalistic practice. For that reason, there are other occasions for using a Mikwèh which are voluntary and done for purely spiritual purposes. As an example, some grooms visit the Mikwèh on the day before their wedding. In addition, many Jewish men (and some women) visit a Mikwèh on the day before Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement). Others practice this custom even before other Jewish holidays, some every week before the start of Shabbat and few individuals go early every day before morning prayers. As was alluded to before, there is a strong spiritual component to this practice. For one thing, a Mikwèh can be seen as representing the waters of creation, or/and a mother’s womb, while immersing and coming out of a Mikwèh symbolizes rebirth and spiritual renewal, or even resurrection. Therefore, it is not surprising to find that a rather new application of the Mikwèh has emerged in our days, namely as a tool within certain post-trauma therapies. Historically: Jews have been building Mikwa’ot for thousands of years. In fact the Mikwèh is such an integral and essential part of Jewish practice that a Jewish community is required to make the building of a Mikwèh their highest priority. A community is required to build a Mikwèh, even before investing in a synagogue! Here are some pictures of Mikwa’ot from (a) Antiquity, from (b) the Middle Ages and from (c) Modern Times. [1] In Hebrew the word is spelled מִקְוֶה. In English this is often transliterated as Mikvèh, while a linguistically more correct (though unusual) spelling is: Miqwèh. One may also encounter the spelling Mikvah, which is based on the wrong understanding of the last vowel of the word to be -ah instead of -èh. The plural of the word is מִקְוָאוׄת (Mikwa’ot), usually rendered as Mikva’ot (erroneously Mikvas) and linguistically most correct: Miqwa’oth. In this article I will use Mikwèh and Mikwa’ot. |

- Personal

-

JUDAISM

- Judaism - Introduction

-

Jewish History

>

- Paleo Hebrew

- The Pentateuch

- Stories of Creation

- Stories of the Flood

- J and E compared

- Priestly Writings

- Prophets of Israel and Judah

- Biblical Poetry

- Hellenism and the Septuagint

- Flavius Josephus

- The Dead Sea Scrolls

- Midrash

- Oral Torah and Talmud

- Origins of Christian Anti-Jewish Attitudes

- Byzantine Jews Before the Advent of Islam

- Yannai

- Jews Under Islam

- Byzantine Jews After the Advent of Islam

- Qara'ites

- Saadia Gaon

- Saadia Gaon's Poem Telóf Tèlef

- Salmón ben Yeruḥám

- Hasdai ibn Shaprut

- Yoséf ibn Abiṭúr

- Andalusian Poetry

- Samuel haNagîd and Ibn Gabirol

- Christian-Jewish Polemics

- The Crusades and Maoz Tzur

- Rashi

- The Tosafists

- Yehuda haLevi

- Ritual Murder and Blood Libel

- The Ḥasidé Ashkenaz

- Toledot Yeshu

- Moses Maimonides, Philosopher

- Moses Maimonides, Rabbi, Leader, Physician

- Abraham Maimonides

- Maimonidean Controversies

- Host Desecration Libels

- The Barcelona Disputation

- Qabbala and the Zohar

- The Cairo Geniza

- The New Sephardi Identity

- David Reubeni and Shelomo Molkho

- Shabbatai Tzevi

- Da Costa and Spinoza

- Yiddish Texts

- Ḥasidism

- The Jewish Enlightenment

- Modern Jewish Thinkers

- Jewish Thought >

- Jewish Law >

- Scripture

-

Liturgy

- Daily Prayers

- Shabbat >

- Rosh Ḥodesh (New Moon)

- Shabbat Rosh Ḥodesh >

- Shabbat Zakhor

- Purim

- Passover/Pesach >

- Omer Counting

- Shabu'oth >

- Tish'a beAbh Evening Service

- The Month of Elul

- Rosh haShana (New Year) >

- Shabbat Teshubá

- Yom Kippur

- Sukkot (Festival of Booths) >

- Sheminí ʻAṣèreth

- Simḥàt Torah

- Ḥanukka >

- CHRISTIANITY

- ISLAM

- (DIS)COURSES

-

OTHER LANGUAGES

- UGANDA

- Contact

- Personal

-

JUDAISM

- Judaism - Introduction

-

Jewish History

>

- Paleo Hebrew

- The Pentateuch

- Stories of Creation

- Stories of the Flood

- J and E compared

- Priestly Writings

- Prophets of Israel and Judah

- Biblical Poetry

- Hellenism and the Septuagint

- Flavius Josephus

- The Dead Sea Scrolls

- Midrash

- Oral Torah and Talmud

- Origins of Christian Anti-Jewish Attitudes

- Byzantine Jews Before the Advent of Islam

- Yannai

- Jews Under Islam

- Byzantine Jews After the Advent of Islam

- Qara'ites

- Saadia Gaon

- Saadia Gaon's Poem Telóf Tèlef

- Salmón ben Yeruḥám

- Hasdai ibn Shaprut

- Yoséf ibn Abiṭúr

- Andalusian Poetry

- Samuel haNagîd and Ibn Gabirol

- Christian-Jewish Polemics

- The Crusades and Maoz Tzur

- Rashi

- The Tosafists

- Yehuda haLevi

- Ritual Murder and Blood Libel

- The Ḥasidé Ashkenaz

- Toledot Yeshu

- Moses Maimonides, Philosopher

- Moses Maimonides, Rabbi, Leader, Physician

- Abraham Maimonides

- Maimonidean Controversies

- Host Desecration Libels

- The Barcelona Disputation

- Qabbala and the Zohar

- The Cairo Geniza

- The New Sephardi Identity

- David Reubeni and Shelomo Molkho

- Shabbatai Tzevi

- Da Costa and Spinoza

- Yiddish Texts

- Ḥasidism

- The Jewish Enlightenment

- Modern Jewish Thinkers

- Jewish Thought >

- Jewish Law >

- Scripture

-

Liturgy

- Daily Prayers

- Shabbat >

- Rosh Ḥodesh (New Moon)

- Shabbat Rosh Ḥodesh >

- Shabbat Zakhor

- Purim

- Passover/Pesach >

- Omer Counting

- Shabu'oth >

- Tish'a beAbh Evening Service

- The Month of Elul

- Rosh haShana (New Year) >

- Shabbat Teshubá

- Yom Kippur

- Sukkot (Festival of Booths) >

- Sheminí ʻAṣèreth

- Simḥàt Torah

- Ḥanukka >

- CHRISTIANITY

- ISLAM

- (DIS)COURSES

-

OTHER LANGUAGES

- UGANDA

- Contact