My Journey to Judaism

I was born and raised in a small village in a Calvinist region of the Netherlands, amidst almost every stereotype that is often used to describe the Dutch countryside: small houses, pastures with cows, dikes, windmills, wooden shoes, and canals.

...small houses, pastures with cows, dikes, windmills...

CALVINISM

I grew up in an area where Calvinism was the dominant persuasion. My family was also Calvinist, be it in a moderate way. This consisted of praying before and after each meal, and reading a piece from the Bible before saying grace.

Our Sundays were mostly characterized by uncomfortable clothes, going to church and Sunday school, and visiting family. Outside of our home, I was exposed to stricter forms of Calvinism. Some children I knew were not allowed to play outside on Sundays. Members of the stricter denominations would not drive a car or ride a bicycle on Sunday. They were also recognizable by their dress code: the women were not allowed to cut their hair short (and would often wear their hair in a bun), they would cover their head when going to church, and never wear pants. Some strict Calvinists would only wear black clothes all week long. By wearing black, strict Calvinists expressed their full awareness of deep and total sinfulness.

Many strict Calvinists would only wear black clothes...

Calvinism teaches that one needs to repent in order to be saved, but it is not in the power of man to do that. One cannot repent himself but has to be repented by God. Calvinists traditionally believe in predestination. Thus, even before the world was created, God had already decided who was going to be repented and saved, and who was going to go to hell. And there is nothing one can do to change that decision.

Very early on, I heard from neighbors, my Kindergarten teacher, and later in Elementary School about the sinfulness of men and the punishments of hell. I recall conversations with my grandmother, a very pious woman, when she told me that a real place in heaven was perhaps too much for her to expect—if only she could stand by the doorpost and look inside!

If only she could stand by the doorpost!

Interestingly, because of constantly reading, telling, preaching and repeating the Biblical stories, especially the stories of the Torah and Prophets, Calvinists often feel a strong connection with the ancient people of Israel.

As a young child I always felt very close to God. I loved the stories about Abraham, Jacob, David, and Daniel. They were my heroes, and the God of Israel was my God. Even though I had been fascinated with the concept of hell and impressed with the sincerity and piety of some of the people I knew, I never believed I would be damned for eternity myself.

As a young child I always felt very close to God. I loved the stories about Abraham, Jacob, David, and Daniel. They were my heroes, and the God of Israel was my God. Even though I had been fascinated with the concept of hell and impressed with the sincerity and piety of some of the people I knew, I never believed I would be damned for eternity myself.

EVANGELICAL CHRISTIANITY

ِِAs a teenager, I somewhat lost my spiritual connection. My family had ceased to pray and go to church, and I felt that something was missing in my life.

When I was about fifteen years old, I came into contact with the Evangelical movement. Like Calvinists, Evangelicals are Protestants who accept the Bible as the word of God and the absolute, infallible source of Divine guidance. Their theology, though, differs from Calvinism in a number of ways. I was told by the Evangelicals that if I would give myself to God and sincerely accept His redemption, I would be forgiven all my sins and truly become His child. This message allowed me to recover my spiritual connection. I was overwhelmed with the feeling that God received me and loved me, that I was His and He was mine. Later, I was taught that this is what is meant when one is said to be "reborn."

When I was about fifteen years old, I came into contact with the Evangelical movement. Like Calvinists, Evangelicals are Protestants who accept the Bible as the word of God and the absolute, infallible source of Divine guidance. Their theology, though, differs from Calvinism in a number of ways. I was told by the Evangelicals that if I would give myself to God and sincerely accept His redemption, I would be forgiven all my sins and truly become His child. This message allowed me to recover my spiritual connection. I was overwhelmed with the feeling that God received me and loved me, that I was His and He was mine. Later, I was taught that this is what is meant when one is said to be "reborn."

I was overwhelmed with the feeling that God received me and loved me

The Evangelical movement provided me with a way to activate and channel my spiritual energy and made me feel part of a larger, worldwide special community.

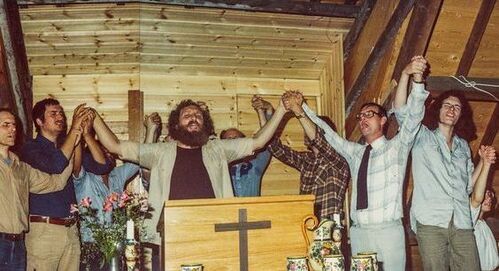

At Evangelical meetings, there was a strong belief that God was truly present, just as real as He had been in Biblical times. People sang in exaltation, raising their hands, speaking in tongues, prophesying, having mystical experiences. These ecstatic experiences were felt to be a constant proof that it was all real and true. In the Evangelical movement there was a strong belief that God would do spectacular miracles for the faithful, including wondrous healings. Although I had ample reason to doubt the seeming miracles of healing, I knew no better way to maintain my relationship with God than through this community.

At Evangelical meetings, there was a strong belief that God was truly present, just as real as He had been in Biblical times. People sang in exaltation, raising their hands, speaking in tongues, prophesying, having mystical experiences. These ecstatic experiences were felt to be a constant proof that it was all real and true. In the Evangelical movement there was a strong belief that God would do spectacular miracles for the faithful, including wondrous healings. Although I had ample reason to doubt the seeming miracles of healing, I knew no better way to maintain my relationship with God than through this community.

There was a strong belief that God would do spectacular miracles for the faithful

Living a life dedicated to God was somewhat of a problem, because the message of the Evangelists was just too simple. To attain salvation, all one needed was faith. Fine! But then what? If I want to dedicate my life to God, how do I do that? The problem here is that Christianity stresses faith, not mitzwoth (commandments).

(In Judaism, it is easier to find direction. If you want to be in God's service, there is no question what you can do. There are numerous mitzwoth waiting to be practiced: Shabbat, dietary laws, holidays, family purity, Torah study, etc. But in Christianity, this structure was lost with the words of the apostle Paul, who claimed that "man is justified by faith, and not by the works of the Law.")

Evangelicals, lacking a structure of mitzwoth, often channeled their religious energy by stressing the obligation of preaching the Gospel and converting people to Christianity. Since this was the framework in which I then lived, I, too, preached the Gospel, going from door to door. I participated in missionary groups, singing and preaching on the streets. I tried to influence Muslims and members of my own family. I spent an entire year in a "Training school for Discipleship", which entailed four months of full-time outreach to high school students. I taught children in Sunday school, and I also gave Bible classes for adults.

(In Judaism, it is easier to find direction. If you want to be in God's service, there is no question what you can do. There are numerous mitzwoth waiting to be practiced: Shabbat, dietary laws, holidays, family purity, Torah study, etc. But in Christianity, this structure was lost with the words of the apostle Paul, who claimed that "man is justified by faith, and not by the works of the Law.")

Evangelicals, lacking a structure of mitzwoth, often channeled their religious energy by stressing the obligation of preaching the Gospel and converting people to Christianity. Since this was the framework in which I then lived, I, too, preached the Gospel, going from door to door. I participated in missionary groups, singing and preaching on the streets. I tried to influence Muslims and members of my own family. I spent an entire year in a "Training school for Discipleship", which entailed four months of full-time outreach to high school students. I taught children in Sunday school, and I also gave Bible classes for adults.

I participated in missionary groups, singing and preaching on the streets

But despite my intense involvement, I was still not spiritually satisfied. I remember praying to God: "What is Your will for my life? How can I fully serve You?" I remember that at that time I had a discussion about Judaism. My thoughts then were: For a Jew it must be so easy. They have the Torah and know exactly what to do!

As I grew older, my doubts about the Evangelical movement also increased. I witnessed preachers who manipulated people's feelings. Sometimes miracles were clearly non-existent and at other times they could be explained differently. More importantly, I did not see any major qualitative difference in the world due to bringing people into the Evangelical community. The only change I could see was that ordinary unsaved people now became ordinary hallelujah-singing saved people. I also wondered about the correctness of the teaching that only those who accepted Christianity were accepted God, while all others, some of whom could not embrace the Christian message because of honest and genuine objections, were doomed to hell. Would God punish a person forever for being honest and for thinking critically before embracing a faith? Moreover, the focus of Christianity was exclusively on being saved or not being saved, in the next world. But was there not significance to this life as well, to the here and now?

Only those who accepted Christianity would be saved by God, while all others were doomed to hell

I became more and more interested in the idea of living by the commandments found in the Torah. In the Christian Bible, Paul wrote that one can only be saved by grace, not by fulfilling the law. For this reason, traditionally, Christian scholars are strongly opposed to practicing any of the Old Testament commandments. But what if one decided to keep these rules not to "earn salvation" but out of love for God? For Christians, since the Torah was part of the Bible and therefore the Word of God, would it not be natural for those who live close to God, to follow the commandments of the Torah?

The Christian argument that God had abrogated the laws of the Torah is peculiar. After all, how reliable was God if He cast aside the Torah which attests to its own the eternal validity? If He can change His mind once after first declaring that the commandments of the Torah were part of an eternal covenant, what is to prevent Him from changing it again? What is the possibility of attaining religious certainty if the Almighty Himself is so inconsistent?

The Christian argument that God had abrogated the laws of the Torah is peculiar. After all, how reliable was God if He cast aside the Torah which attests to its own the eternal validity? If He can change His mind once after first declaring that the commandments of the Torah were part of an eternal covenant, what is to prevent Him from changing it again? What is the possibility of attaining religious certainty if the Almighty Himself is so inconsistent?

If the Torah was the word of God, shouldn't it be natural to live by its commandments?

Remarkably, Jesus himself had announced that the Torah would not be abolished. He said: “Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them. For truly I tell you, until heaven and earth disappear, not the smallest letter, not the least stroke of a pen, will by any means disappear from the Law until everything is accomplished. Therefore, anyone who sets aside one of the least of these commands and teaches others accordingly will be called least in the kingdom of heaven, but whoever practices and teaches these commands will be called great in the kingdom of heaven. (Matthew 5: 17-19)

ISLAM

Before proceeding with this essay, I want to describe another aspect of the village in which I grew up. Our neighborhood had many Moroccan immigrants. Having grown up in close contact with these Arab and Berber Muslims, I decided to enroll in the University of Leiden and study Arabic and Islam. Islam and Islamic culture intrigued me. Particularly attractive to me was the beauty of Islamic prayer.

As I pursued my study of Islam, my struggle with Christian theology intensified. While Christianity believes that one can only come to God through Jesus, Islam teaches that anyone can pray directly to God without the need for an intermediary. This made sense. If God is all-powerful, surely, He can forgive penitents without needing anybody to die for someone else's sins. Islam's emphasis on pure monotheism made more sense than the Christian idea of the Trinity. Quite significantly, Islam and Judaism are very similar in these subjects.

Islam and Judaism are very similar in their approach of monotheism

I was also interested in the Muslim community because it had not suffered from structural secularization in the same way as the Christian world. The (Protestant) Christian approach of building its community based on a common belief alone (by faith and not by works)does not seem to work well. Since people will always have their individual opinions, they will believe and doubt in individual ways. This makes a community based on faith alone subject to disruption and dissolution, except if it tries - God forbid - to suppress the believers' mental aptitude for free and critical thinking (which, of course, has been tried all throughout history). On the other hand, a community not only built on faith but primarily on common religious practices could hold people together more effectively without limiting their creative thinking.

Although I occasionally joined in Muslim prayer and participated in Sufi rituals a few times, I never seriously considered joining Islam for several reasons. As a start, Muslims are obligated to believe in the Torah, the Psalms, and the Gospel as divine texts previously revealed by God. But the contents of the Qur'an are often at odds with these texts which it claims to confirm. The discrepancies between the Qur'an and these older sacred texts present an obvious problem. Because they contradict each other, they cannot be all correct and of divine origin. To explain the differences and to address any allegations of mistakes in the Qur'an, Islamic scholars accuse the Jews and Christians for having altered their own holy texts! This is how Muslims can (theoretically) believe in the holy books of Judaism and Christianity and (in practice) reject them at the same time. Any contradiction between the Bible and Islam is explained in this way. According to the early Islamic scholars, the ‘People of the Book’ changed their Scriptures during the days of Muhammad. For example, they supposedly removed all sections that predicted the advent of Muhammad and his mission. However, in more recent history, large numbers of ancient manuscripts of the Jewish Bible have been found that date back many centuries before the age of Muhammad which do not contain such verses.

Furthermore, Muslims argue that God revealed the Torah to the Israelites but later rejected them for their sins. He then gave the Gospel to the Christians, but they sinned as well and were consequently also rejected. Finally, God sent down the Qur'an. According to this way of thinking, though, one could argue that God - who has already changed His message several times - may well change His instructions yet another time, even if God has declared, according to Islam, that this religion will never be replaced again. After all, He had also declared in the Torah that its instructions would be immutable and valid forever but nevertheless replaced the Torah with something else. Therefore, even if Islam is right, the Qur'an may not remain God’s final word.

Muslims argue that God first gave the Torah and later the Gospel but finally He gave the Qur'an

I also noticed that the Qur'an contains inaccuracies about Judaism and Christianity. It blames the Jews for saying that Ezra is the son of God (something that no Jew believes). When it accuses Christians for believing in three deities, i.e. God, Jesus and Mary, it shows a misconception of the Christian teaching of the Trinity which is that the one God reveals Himself as three persons: the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. Of course, it could be argued that the Qur'an may refer here to certain Jewish and Christian sects and not to regular Jews and Christians. However, it doesn’t say so, and as a result of these statements, these accusations have been made throughout Islamic history against Jews and Christians up to the present day.

Another reason that I felt uncomfortable with the Qur'an was the way it threatens nonbelievers with the punishment of hellfire and grants Paradise only for the true believers, quite comparably to traditional Christianity. One will not find such threats of hell in the Torah or the Hebrew Bible. I believe that God is greater than any single religion. We can find good and upright people in each community, even if their theological beliefs may be far from the truth. And the opposite is true as well. Even though I deeply believe in God myself, would the Almighty really be upset if someone cannot imagine His existence? Would believing or not-believing in God even affect Him? Would the Creator of the universe not have understanding and compassion?

Besides, threats and promises are not the purest motivators for proper religious life. If God is just and merciful, will He punish His creatures forever because of erroneous beliefs or because of sins they committed only temporarily during their short lives? Punishment can sometimes be useful as a means of education so that one can learn from one’s mistakes. But what is the use of an eternal, painful punishment when there is no chance of repentance and self-improvement? Would this characterize God as merciful and compassionate or utterly cruel? By contrast, the Torah does not mention hell at all, and Jewish teachings of the Hereafter are the result of rabbinic reasoning.

Besides, threats and promises are not the purest motivators for proper religious life. If God is just and merciful, will He punish His creatures forever because of erroneous beliefs or because of sins they committed only temporarily during their short lives? Punishment can sometimes be useful as a means of education so that one can learn from one’s mistakes. But what is the use of an eternal, painful punishment when there is no chance of repentance and self-improvement? Would this characterize God as merciful and compassionate or utterly cruel? By contrast, the Torah does not mention hell at all, and Jewish teachings of the Hereafter are the result of rabbinic reasoning.

At this point I would like to clarify that I do not want to put down Islam, Christianity or any other religion. These religions have great beauty and value, and they give meaning and comfort to the lives of millions of people. I do not want to take that from anyone - God forbid. My only goal is to explain my personal motives for the choices I have made in my life.

TORAH

Because both Christianity and Islam accept the divine origin and authority of Jewish scriptures, was not the oldest revelation (the Torah) in fact the foundation of these religions? If we assume that God does not contradict Himself, and if the Torah was given first, then any sacred text revealed after the Torah cannot contradict it. Furthermore, as all later books (of Christianity and Islam) refer to the Torah as authentic, if the Torah is not true, then these later books cannot be reliable either. In other words, if any of these holy books is divine and true, it must be the first one. Having reached this conclusion, I decided to focus on the oldest source: the Torah.

I decided to go to the original source: the Torah

At this point in my life, I had not met even one Jew. I stopped going to church and started to reread the Torah while looking for ways to practice the laws that I had read so many times but discarded. I began to observe a day of rest on Saturday instead of Sunday. I stopped eating foods forbidden in the Torah. But I often did not know how to implement the commandments in practice. I quickly realized that I did not need to study the Bible in a vacuum and reinvent the wheel. There was a community with many centuries of experience in fulfilling the words of the Torah: the Jewish people. Therefore, I started to read books on Judaism. I took Hebrew classes at the university (mainly Biblical Hebrew and grammar), as well as courses on Jewish law and history. I also began to attend Shabbat services in a synagogue.

There was a community that had many centuries of experience with the Torah: the Jewish people

Soon after I started interacting with the Jewish community in the Netherlands, I discovered a few things. The Dutch Jewish community was very small and (especially the older generation) was still much traumatized by World War II. This may be one of the reasons why the rabbis in the Netherlands were extremely reluctant to allow converts. The practice was that a candidate for conversion had to be approved by all the main rabbis in the country, something that rarely happened. At the same time, though, there were many people in the Netherlands who wanted to convert to Judaism. I personally knew people who had been studying for more than ten years, living observant lives, keeping kosher, and so on, but who were still not accepted into the Jewish community. My impression was that to be accepted, it would likely not be enough to embrace Torah and Judaism but also to seamlessly fit into the mold of stereotypical Orthodoxy. I realized that if I wanted to become Jewish, the price would be extremely high, and I might be forced to sacrifice my individuality. Did I want that?

If one wants to join the Jewish people, one must accept Judaism as a whole. You cannot pick and choose what to accept and what not, at least not as far as the essential Jewish teachings are concerned. But having grown up in the scriptural tradition of Protestantism, (which teaches “Sola Scriptura”; Scripture Only), I could not embrace the idea of an Oral Torah. I could not believe that there was an extra-scriptural Torah tradition with the same authority as the text itself. I was not ready to accept this concept.

NOACHIDES

Although I didn't see any possibility of becoming Jewish, partially because of my family situation, I was determined to serve God and to follow the Torah. I decided to follow the literal text as closely as possible, while looking for different interpretation as to how the commandments could be fulfilled by a non-Jew. This was a lonely position. Christians thought I was a Jew, and Jews viewed me as a Christian. This loneliness was not just spiritual but especially social. How could anyone celebrate Shabbat or holidays without a community? I hoped and prayed that I would meet like-minded companions. Fortunately, I did meet them—people of different backgrounds, from different parts of the country, even from abroad. Each of us had thought that we were the only ones to have found our way to Torah without being Jewish. I remember the first time we came together—about seven or eight of us—in Amsterdam. We were happy and thrilled to have found others who shared our religious predicament. That meeting was the actual birth of a Noahide movement in the Netherlands. The term Noahides stands for non-Jews who follow the Torah and keep the universal commandments that apply to the descendants of Noah (everyone).

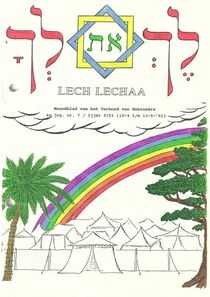

I published a monthly magazine named "Lech Lechaa" and organized an annual Noah Day

Our group originally called itself the "Alliance of Abraham." Just as Abraham had left his background, his old (pagan) religion and his culture to become a Hebrew (someone who crosses over to the other side to a land not yet known), likewise we had left our backgrounds behind for a yet unknown destination. Later we changed the name to "Alliance of Hebrews" and eventually to "Alliance of Noahides," meaning that our basis would be the Seven Laws of Noah, described in Jewish tradition as God's moral code given to the non-Jewish world. I published a monthly magazine named "Lech Lechaa", meaning in Hebrew: "Go for yourself!" Lech Lechaa is the name of a section in the Torah and the first words of God spoken to Abraham when He ordered him to leave his family and set off on a journey. I organized an annual Noah Day with festivities around the time that Noah had left the ark, and I organized conferences with various speakers, including rabbis, scholars, philosophers and others.

According to Judaism, the seven Noachide laws that all people are to abide by, are: 1) No idolatry, 2) No blasphemy, 3) No sexual immorality, 4) No murder, 5) No robbery, 6) Not to eat meat taken from a living animal (no cruelty of animals), 7) Establishing justice through courts.

However beautiful and important these rules may be, it is difficult to build an identity and a community only on the basis of the Noahide laws. We revere God, we don't murder, we don't steal. That’s wonderful, but are these rules of conduct so extraordinary that people would want to join such a movement, so you can build a religious community? A religious community needs more than basic laws of ethics. It needs a way to worship, to celebrate life-cycle events. It needs a religious structure for daily life.

However beautiful and important these rules may be, it is difficult to build an identity and a community only on the basis of the Noahide laws. We revere God, we don't murder, we don't steal. That’s wonderful, but are these rules of conduct so extraordinary that people would want to join such a movement, so you can build a religious community? A religious community needs more than basic laws of ethics. It needs a way to worship, to celebrate life-cycle events. It needs a religious structure for daily life.

It turned out that the people who identified with our Noahide movement were not united in their goals and expectations. Some of our group wanted to develop their own traditions and customs based on Torah commandments but as an alternative to traditional Judaism. Others hoped eventually to convert to Judaism, and they used our community to prepare conversion. And again, others were perfectly happy just keeping the Seven Laws of Noah and tasting bits and pieces of Jewish culture.

A religious community needs a way to worship, to celebrate life-cycle events

I designed an organizational structure that would allow everyone to develop his or her own identity. Every member of our group accepted monotheism as defined in Judaism and the Seven Laws of Noah. But we also had subgroups—called tents—each with its own specific ideals and activities. We imagined that Abraham himself had traveled with a diverse group of people who came together to form one camp. Each subgroup appointed a delegate to a "Council of Tents". We also had an Advisory Council composed of Jews faithful to rabbinic Judaism who supported our efforts.

HEBREWS

I was part of the group that wanted to develop its own traditions, rituals, and prayers. To do this, I not only studied the Torah according to the Rabbinic Jewish tradition but also alternative groups like the Qara’ites and the Samaritans. I studied their texts and visited their communities. I spent several Sabbaths with the Samaritans on Mount Gerizim and witnessed the bringing of the Passover sacrifices. I prostrated myself in their synagogues and in those of the Qara’ites.

I spent several Sabbaths with the Samaritans on Mount Gerizim, and witnessed their Passover sacrifices

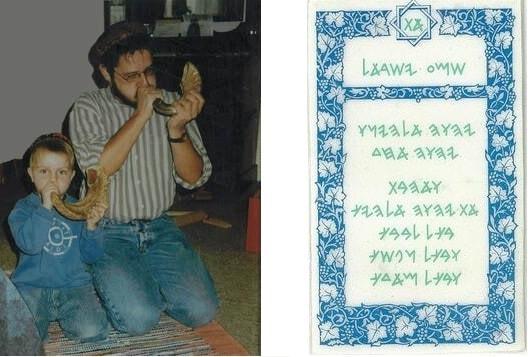

In consultation with others, I worked on developing new ways for our small community to practice the Torah. I believed that the rabbinical interpretation of the Torah was one possible way to interpret and practice the commandments, but that there were other possibilities to fulfill the literal meaning of the text, ways that could be followed by people from other communities. I composed a Grace after Meals, prayers for the days of the week, the Sabbath and the holidays, and I developed rituals that were different from traditional Judaism. For example, we would not light fire on Shabbat (later, we extended this to electric light), but we permitted transporting or extinguishing fire. We celebrated Passover with a stick in our hand and ate roasted lamb. We always celebrated Shabuoth on a Sunday, like the Qara’ites. I wrote a daily prayer book, entirely based on the service in the Mishkan (the desert sanctuary of the ancient Israelites). We even had a place of worship in one of the rooms of my house that was a reflection of the Mishkan (the Tabernacle): curtains all around hanging on rings, supported by copper rods. We had a square tent-like structure opposite the entrance where we burned incense, and a menorah that was lit at certain times. For mezuzoth, we had a card attached to our doorposts with the first two verses of the Shema written in old Hebrew letters.

I was part of the group that developed its own tradition, rituals, and prayers

For all our efforts though, things went wrong. If one bases oneself only on the written Torah, there are many possible ways to interpret the text. Without some kind of authoritative source of interpretation, all our rituals and interpretations were subject to constant change based on fluctuating insights or feelings. Because of so much instability, the community could not hold on to a common, lasting tradition. We had some members who decided to follow a calendar not linked to the moon while others preferred to follow the standard Jewish calendar. Some began to observe the Sabbath only during the daytime, because it is called the Sabbath Day and to celebrate Yom Kippur without fasting. It is hard to determine these options based solely on the text of the written Torah. Then, some even argued that God had rejected the traditional Jews because they followed the rabbis instead of God. This line of thinking was intolerable to me. Eventually, I broke with the group that I had built.

JUDAISM

Over the years, I had continued to study traditional Judaism, and I did some lecturing on Judaism. I also served as the chairman of an organization to restore an old dike-synagogue in my home region (in the village of Sliedrecht). As a result, my identification with Rabbinic Judaism had gradually increased.

I served as chairman to restore an old dike-synagogue

At last, I also began to understand the character and role of the Oral Law.

Firstly, I had clearly seen through my own experience that without the Oral Law the tradition would simply disintegrate. For example, if people follow different calendars, they will celebrate holidays on different days. Even if they choose one calendar, they may still prefer to pray in separate ways and at separate times. They may read different texts, follow different rules and perform on different rituals. In other words, the written text provides many possibilities for interpretation so that a community collapses if there is no accepted and common tradition on the essential elements of religion practice.

Secondly, I realized that the Talmudic tradition is not really extra-scriptural but rooted in authority given to the rabbis by Scripture itself. In the Torah, Moses is instructed to appoint a council of seventy elders (later called the Sanhedrin) which was to make binding decisions. The authority of the rabbis of the Talmud, the descendants of these first elders, is thus part of the written Torah itself.

Thirdly, I realized that nobody can practice the Torah outside of the Jewish people. Ruth had first told Naomi, "your people are my people" and only then stated, "your God is my God". We can only fully serve the God of Israel by being part of the people of Israel.

Firstly, I had clearly seen through my own experience that without the Oral Law the tradition would simply disintegrate. For example, if people follow different calendars, they will celebrate holidays on different days. Even if they choose one calendar, they may still prefer to pray in separate ways and at separate times. They may read different texts, follow different rules and perform on different rituals. In other words, the written text provides many possibilities for interpretation so that a community collapses if there is no accepted and common tradition on the essential elements of religion practice.

Secondly, I realized that the Talmudic tradition is not really extra-scriptural but rooted in authority given to the rabbis by Scripture itself. In the Torah, Moses is instructed to appoint a council of seventy elders (later called the Sanhedrin) which was to make binding decisions. The authority of the rabbis of the Talmud, the descendants of these first elders, is thus part of the written Torah itself.

Thirdly, I realized that nobody can practice the Torah outside of the Jewish people. Ruth had first told Naomi, "your people are my people" and only then stated, "your God is my God". We can only fully serve the God of Israel by being part of the people of Israel.

Most Jews are born into Judaism. But strangely enough, some people must go through complicated and long detours. It is believed that someone who converts to Judaism was born with a Jewish soul that is restless until it finds its way back to Judaism. I do not know if this is true in the literal sense, but I do believe that God has led me through unusual paths and guided me home. To fulfill my decision to convert, I needed to travel to New York. The rabbis in Holland had created barriers that were all but impossible for me to transcend. I first met with an Orthodox rabbi whose goal seemed to be to prove that I was not a valid candidate for conversion. He asked me various questions, many of them quite technical, until he found things that I did not know despite my many years of study. By the way, I never claimed to know all the Torah and Talmud; only that I had studied much and was prepared to keep learning and observing the mitzwoth (the commandments). The meeting was quite frustrating since I had genuinely hoped to receive a warmer welcome and greater encouragement. I also did not know if this route would be permanently closed for me and if I would ever find an open door. Friends recommended that I meet with another Orthodox rabbi, and I did so. This rabbi was considerably more receptive, and very much appreciated the long spiritual struggle and study that had led to my decision to convert. To abbreviate a much longer story, after having satisfied himself that I was indeed a sincere candidate for conversion, and that I had accepted upon myself the "yoke of the commandments" of the Torah, he convened a Beth Din (a religious court) to oversee the technical aspects of the conversion. Finally, I became a member of the Jewish people.

"Lech Lechaa"... the same name I had once chosen for the magazine I used to publish

The first Shabbat after my conversion, I had the honor to read a section from the Torah in the synagogue. The section of that week was the Parasha "Lech Lechaa", the same name as I had once chosen for the magazine I used to publish. It recounted Abraham's journey with God, the story that had originally inspired me to set out on my own journey. As I read the Torah, I felt that I had followed in the footsteps of Abraham our father who had inspired another believer to find his true destination.

This article is an edited version of the original published in: Rabbi Marc D. Angel, "Choosing to be Jewish", The Orthodox Road to Conversion", Jersey City (Ktav) 2005