|

|

Robert Chazan,

| |||||

|

|

“[Peter] brought with him a letter from France, from the Jews [there], [indicating] that in all places where his foot would tread, and where he would encounter Jews, they should give him provisions for the way. He would then speak well on behalf of Israel [i.e. the Jews], for he was a priest, and his words were listened to.”

|

This source suggests that Jews in France developed a strategy for dealing with Peter and this strategy – for their Rhineland brothers to give him economic assistance- seems to have worked.

Though the anti-Jewish sentiments that went along with the First Crusade were based on the New Testament’s narrative of the Jews’ murdering of Jesus and on calls for Christian revenge, by the middle of the twelfth century, the dominant perception of Jews was that they were enemies of Christianity here-and-now, and that they were always inclined to bring harm to Christian society. This lead the militant and influential abbot Peter the Venerable of Cluny to urge the king of France to let the Jews pay for part of the expenses of the Second Crusade because of their never-ending hatred of Christianity and their blasphemy against the Christian faith.

The most dangerous outgrowth of this notion of ongoing Jewish hatred and hostility was the belief that Jews regularly murdered Christian neighbors in secret. In most of such cases, the alleged victim was a (defenseless and innocent) child. Such murder accusations came up all over northern Europe during the mid-twelfth century. This quickly grew into a conviction that these murders were committed out of religious motives and that the victims were therefore Christian martyrs. This further evolved into allegations of ritualized murder such as claims that killings were done by crucifixion or as part of a renewed Jewish sacrificial cult.

In 1171, an unusual case of Jewish murder accusation took place in the town of Blois. The incident in Blois was unusual in several ways: Firstly, there was never a Christian corpse. Secondly, the local ruler, Count Theobald of Blois, accepted the allegation without evidence and ordered a so-called ‘trial by ordeal’. A trial by ordeal meant putting someone through a test, such as throwing the accused in water to see if he or she would float or sink. Such a superstitious way of testing if someone was guilty was quite common at the time. Based on this ‘ordeal’, the Jews were convicted and more than thirty of them were executed. The incident caused deep fear among the Jews of northern France who were afraid that this conviction would further fuel the idea that Jews were murderous people.

To counter the threat, the Jews of northern France organized a campaign by carefully investigating all events that had taken place in Blois in order to disprove the accusations and to persuade the northern French authorities to dismiss the charge. Both Count Henry of Champagne – the brother of Count Theobald – and King Louis VII – his brother-in-law – rejected the murder allegation. During a meeting with the Jewish leaders, the king distanced himself from Count Theobald’s actions and reassured his frightened Jews: “Be aware, all you Jews of my land, that I harbor no such suspicions. Even if a body be discovered in the city or the countryside, I shall say nothing to the Jews in that regard. Therefore, be not frightened over this matter.” This message was distributed to royal officials throughout the king’s domain by a written charter.

The statement of the king after the events of Blois shows the general position of the ruling class of northern class of northern France. Except for the incident in Rouen, the Jews of northern France seem to have been well protected by their lords during the First Crusade. This in stark contrast with the loss of Jewish lives further eastward in the Rhineland. At the beginning of the Second Crusade, the authorities of both Church and state, as well as the Jews themselves, were all very much aware of the grave dangers for the Jews that went hand-in-hand with crusading. The important spiritual leader behind the Second Crusade, Bernard of Clairvaux, while he was campaigning for the Crusade and recruiting Christian warriors, also warned against inflicting violence upon the Jews. As a result, Ephraim of Bonn, who documented the events of the Second Crusade, had little violence to report, even for areas in the Rhineland.

Ephraim describes one frightening incident in which the life of Rabbi Jacob ben Meir, a Jewish leader in northern France, was threatened and then saved. After describing the incident, Ephraim adds: “In the rest of the communities in France, we have not heard of anyone killed or forcibly converted. However, the Jews lost much of their wealth, for the king of France commanded: ‘All who volunteer to go to Jerusalem shall have their debts forgiven if they are indebted to the Jews.’ Since most of the Jews’ loans are by charter [i.e. with no security deposit], they lost their monies.” Even though there were some allegations of Jewish murder during the second half of the twelfth century, it seems that the rulers of northern France effectively protected the Jews; there are no reports of the loss of Jewish lives by angry mobs.

However, there were two notable occasions where rulers of northern France turned against the Jews. For example, we already saw the incident of Blois in 1171 where Count Theobald of Blois was responsible for the death of more than thirty Jews. One of the Hebrew letters mentioned above suggests the complicated combination of romantic and political circumstances behind the court of Blois’ unusual actions of killing the Jews. There was another case in which Philip Augustus, the young king of France at the time, initiated an assault that killed more than eighty Jews living in an area next to the territory belonging to the French royalty. The attack was based on assumptions of Jewish murder and the notion that King Philip Augustus needed to set matters straight. There also may have been political motivations. In any case, the actions of Count Theobald of Blois and King Philip Augusts were exceptions to the rules. For the most part, the rulers of northern France protected their Jews effectively throughout the stormy twelfth century.

Even as a minority group, the Jews of northern France were able to increasingly flourish in their spiritual endeavors throughout the eleventh and twelfth centuries. The heart of Jewish organizational life lay in the way the local community were organized. We lack details, but it is clear that the local Jewish communities of northern France developed effective systems of taxation and law enforcement, already during the eleventh century.

During the twelfth century, the Jews of Northern France realized that they needed to organize and defend themselves more efficiently. The Blois incident shows that the Jews of northern France were able to organize themselves on a broader level than just locally and thereby achieve some successes through negotiating with the leaders of the Church and with local rulers. One important figure heavily involved in this was Rabbi Jacob ben Meir who lived in Ramerupt, in the county of Champagne. He worked together with the leaders of the Jewish communities of Troyes in Champagne and of Paris and Orleans which were in the domain of the king. Together they approached the king, the counts of Champagne and Blois, and the archbishop of Sens. Developing such a new level of Jewish cooperation turned out to be crucial to Jewish survival in twelfth century northern France which was on the brink changing toward centralization.

Cooperation within the Jewish community was more than just defensive. Rabbi Jacob ben Meir and his brother Rabbi Samuel ben Meir were key players in bringing together representatives from different Jewish communities to set up regulations that helped the Jewish leaders deal with the challenges of the twelfth century. Some of these ordinances that were widely accepted across northern France and beyond have survived. Even though these regulations were in response to issues that were relatively minor compared to the events in Blois, these ordinances show the broad cooperation among Jewish leaders in twelfth century northern France and the important role that Jacob and Samuel ben Meir played. The Jews knew that northern France was making a tremendous change towards centralization and had to take measures to adapt to this big change.

The same creative energy that is evident from success in Jewish business and community organization can be seen in northern French Jewish culture. The creativity found within Jewish culture in eleventh and twelfth century northern France was stimulated by the general environment. While it is relatively easy to show the impact that the medieval Muslim society had on Jewish cultural activity where Muslims and Jews shared a written language and easily understood each other’s writings, in the world of western Christendom where people spoke Romance languages and Latin was the language of literature, it is much more difficult to understand the connections and to recognize the various influences. However, in some areas of southern Europe, such as Italy, it is possible to discern cultural influences, for instance by looking at the poetry of Immanuel of Rome and his innovative style of poetry. For the Jewish cultural creativity in northern Europe which expressed itself in traditional Jewish ways, it is impossible to identify exactly what the impact of the general society was and how it impacted Jewish culture. All we can do is argue that the richness of Jewish creativity must have some sort of relationship with the vibrant surrounding society, and we can point at some parallels in both cultures.

During the eleventh century, a Jewish man named Rabbi Solomon ben Isaac was to become a pioneer in this cluster of young Jewish communities. A native from the town of Troyes, in Champagne (now France), he made the decision to immerse himself in Jewish studies in the most flourishing center of Jewish culture of northern Europe. He traveled eastward to study in the Rhineland and eventually returned to Champagne to share what he had learned. He is now known as Rashi. Rashi was extremely productive; he composed two large commentaries, one on the Bible and one on the Babylonian Talmud. Both works became extremely influential in consequent Jewish life. Possibly the most remarkable about impressive his works is that they were created at such an early stage of a young, emerging community.

Besides for his own influential work, Rashi is also recognized for initiating new trends in talmudic and biblical commentary. These new tendencies would continue for more than a century after his death. His style of talmudic commentary would dominate the study of Talmud from the twelfth through the twenty-first century. The specifics of his commentary style will be discussed later in this book. For now, it is enough to state that the young northern-French Jewish communities were not only innovative in areas of economy and community organization, but at least as much in areas of Jewish cultural and religious life.

Jewish life and creativity in twelfth-century northern France took place amid a dynamic Christian society with lots of political diversity. But that was going to change. During the thirteenth century, northern France became united under the rule of the Capetian kings, who ruled from their capital Paris over ever-larger territories in the north and later also in the south. This change towards a more central government initially was a blessing for the Jews of northern France who had been organized as independent communities in each of the territories they were located. However, centralization would turn out to have major drawbacks. The fate of the Jews now rested upon one ruler. When, in the twelfth century, several rulers in northern France expelled the Jews from their territory, these refugees could easily find new homes in other domains, not too far away and without much economic detriment. But when King Philip the Fair expelled his Jews in the early fourteenth century, a much bigger territory was part of the royal domain, and Jews had to travel much further to find refuge in vastly different societies.

During the rule of King Philip Augustus (1172-1223), northern France and Jewish communities across northern France experienced new developments and concentration of authority. At the beginning of King Philip's reign, he had limited power and resources. In contrast, at the time of his death, he left behind a much larger kingdom, great wealth, and prestige. What King Philip's view and goals were on the Jews is not clear; his policies towards them shifted in unpredictable ways. At the end of the day, King Philip's centralization of authority and his Jewish policies would contribute to the downfall of Jewish communities in Northern France during the thirteenth century.

The poor circumstances of King Philip’s early years on the throne led him to a series of anti-Jewish measurement. In a first move, King Philip seized a wide range of Jewish goods which the Jews could then ‘ransom’ (buy back). This confiscation perhaps indicates how well-off the northern French Jewish communities were economically, as they were perceived as a potential source of financial resources. The monarchy repeated such grabs several times throughout the thirteenth century. A second royal measurement concerned moneylending, a growing Jewish specialization which increasingly evoked hostility. King Philip ordered that debts owed to Jews were forgiven and one-fifth of the debt was to be paid to the royal treasury. In 1182, King Philip banished all Jews from the royal domain, thereby taking possession of Jewish property, while synagogues were handed over to the Church.

While Rigord, in his biography of King Philip, tries to justify all these measurements as reactions to Jewish crimes flowing from Philip’s responsibility as a “most Christian king”, what all these moves had in common was financial gain, catering to the wishes of the Church, and smartly tapping into the sentiments of the general public. In each of these moves, the impoverished monarchy gained significant financial resources. Forgiveness of debt and the transfer of synagogues gave King Philip greater support of the Church. The royal biographer Rigord describes very well how King Philip, through his actions gained greater support. He sees the king’s anti-Jewish moves as among the major achievements of Philip’s earlier years on the throne. Forgiveness of debt to Jews certainly was a popular measurement for those who were in debt. Paying only twenty percent to the treasury instead must have seemed like a good deal. Finally, the expulsion of the Jews was probably popular among many Christians. The same may have been the case when the king attacked the Jewish community of a neighboring territory.

Rigord was delighted about the young king’s anti-Jewish moves but upset when the king decided to readmit the Jews to France in 1198. The change of royal policy was inspired in part because of Jews being on the move after anti-Jewish riots that were sparked by the preaching of Fulk of Neuilly. With Jews wandering from place to place, King Philip decided to attract some of them back to his kingdom, thereby stimulating the economy through Jewish money lending and taxing opportunities associated with Jewish banking.

During the later years of King Philip Augustus, which lasted until 1223, there were three significant developments that affected to the Jews. The first was the quick expansion of the king’s territory, including the removal of the Angevin kingdom, which resulted in more Jews living under his control, protection, and taxation. The king’s influence was even felt in areas that remained independent. King Philip Augustus established new policies for Jewish moneylending which became standard practice in most of northern France, even in independent domains. For instance, in 1206, a new set of rules regarding Jewish moneylending was implemented in the king’s domain and, at the same time, in two other important territories. As a result, Jews could not simply move from one are to another to avoid these new limitations. Philip Augustus used the Jews as a tool to increase his power.

The second development after was stricter control over the Jews, meant to exploit Jewish wealth more effectively. The outcome would eventually be a drastic restriction of Jewish movement and a lowering of the Jews’ status. As we saw, before this point, it had been easy and quite common for Jews to move from place to place. Even during expulsions in 1182 and 1190, Jews were able to cope rather well because they could find refuge in nearby areas. Once Philip readmitted Jews to his domain, he took full control over them. One way he achieved this through a treaty with the count of Champagne where many northern-French Jews lived. The king promised: “We shall retain in our land none of the Jews of (…) Theobald, count of Troyes, unless with the consent of that count.” At the same time, the count made the same promise with respect to the Jews of the king. Each signatory of the treaty was now guaranteed full control of his Jews, and it became extremely hard for Jews to move. After conquering Normandy, Philip made sure to secure his control over its Jews as well. Jews were forced to give guarantee deposits for their continued presence and acceptance of royal control. The result of the king’s strategies was that the Jews became restricted in their movements and more effectively exploited.

The history of Jews after 1198, under Philip Augustus’s reign, marked a significant event that shaped their lives tremendously. In 1210, Jews all over northern France were arrested and their possessions taken away. To get it back, the Jews had to pay exorbitant amounts of money, which put a huge burden on them for years to come. Again, firmer control over the Jews, prevented them from seeking any relief from this crushing abuse.

While the king’s greed lay at the root of the new policy of controlling Jewish movement and occasionally taking away portions of Jewish wealth, there was a third, opposite trend in Philip Augustus’s policies which can be only understood in relation to his commitment to the Church and the need to appease its leaders. As previously noticed, the Church’s concern with Jewish moneylending had increased during the second half of the twelfth century. This concern expressed itself in several ways. For some Church leaders, Jewish moneylending resulted in abuses that had to be addressed and eliminated; for others, Jewish moneylending was principally wrong – Deuteronomy 23:21 could not be read to allow Jews to take interest from Christians. In the court of the Pope, it was the former view that dominated, leading among other things to the edicts of the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215 that prohibited excessive Jewish usury. Excessive seems to have been defined as an interest rate of more than twenty percent per year. As was often the case, the leaders of the Church in northern France leaned towards the more extreme position. We already saw the campaign of Fulk of Neuilly at the end of the twelfth century to eradicate Jewish moneylending altogether, inspired by the idea that Jewish taking of interest was essentially illegal.

Already in 1205, the powerful Pope Innocent III sent a strong letter of rebuke to King Philip Augustus. The first and most striking of the Pope’s complaints concerned Jewish moneylending: “… in the French kingdom, the Jews have become so disrespectful that by means of their dangerous usury, through which they not only charge interest, but even interest upon interest, they take possession of Church goods and Christian possessions. What the prophet said about the Jews is being fulfilled among the Christians: ‘Our heritage has been turned over to strangers, our houses to foreigners.’” The Pope’s complaint does not portray Jewish interest taking as sinful in and of itself; the focus is on the unwelcome consequences of Jewish usury – Jewish confiscation of church vessels and Christian property. Some concessions to the demands of the Church had to be made, and in fact it was.

King Philip Augustus decreed a chain of restrictions on Jewish money lending which severely limited Jewish income from banking. Two powerful figures, the countess of Champagne and the lord of Dampierre, joined forces with the crown and issued an edict in 1206. The most important stipulation of this edict was a maximum interest rate of twenty percent per year, a decree in anticipation of the Fourth Lateran Council (an important assembly of the Catholic Church, held in 1215, that would issue numerous anti-Jewish measurements) . Another stipulation was a prohibition on Jews from collecting their loans within the first year because of an issue the Pope had with compound interest. Towards the end of his rule, in 1219, King Philip Augustus once again addressed the Church’s concerns with Jews and money lending and the consequences it brought to society. In a new set of measurements, King Philip dealt with debts that weighed down the poor people of France as well as Church institutions. are struggling to preserve their society while being indebted to the Jews. These new laws were meant to protect these rather defenseless sectors of French society.

The long rule of Philip Augustus would prove to be a turning point in the development of royal France and for the Jews as well. While his policies show elements of instability, the most severe concerns – enhanced control of the Jews, exploitation of their wealth, and severe limitations of the moneylending business – foreshadowed what was to come. The long and effective rule of Philip Augustus would prove to be the beginning of the decline of Jewish fate in northern France. However, there was no way for the Jews living under his rule to foresee that.

The historian William Chester Jordan describes three phases of the decline that Philip Augustus set in motion: (1) the brief reign of Louis VIII and early years of Louis IX (1223-1242); (2) the mature years of Louis IX and reign of Philip III (1242-1285); (3) the reign of Philip IV and the expulsion (1285-1306). The Jews were readmitted to royal France in 1315, but the real history of Jewish society in medieval northern France really ended with the expulsion of 1306.

In the first of these stages, the often-fluctuating policies introduced under Philip Augustus become more consistent. The two opposing trends of both royal exploitation of Jewish money lending and simultaneously opposing it went hand in hand. At the beginning of Louis VIII’s reign, in 1223, the king ordered that all debts owed to Jews would no longer bear interest and were to be paid off over three years to the royal treasury. This was another confiscation of Jewish wealth while the treasury did not benefit from interest. What is more significant in the long run was a rule that Jews were no longer allowed to seal their debts, which collapsed their system of banking. Jewish lending in northern France had been conducted with the support of local rulers and royal authorities, but this support was now removed. The increasingly religions rulers of northern France wanted to distance themselves completely from Jewish moneylending. These laws were initiated by twenty-six northern-French rulers and came with increased control over the Jews. These rulers were not allowed anymore to admit Jews from other domains. In other words, Jews were no longer able to flee from one area to another.

Seven years later, during the early years of King Louis IX, the French rulers sharpened the trend of 1223 even more. “We (…) shall henceforth enforce no contracted debts to be repaid to the Jews.” Hereby, the king and the local rulers of northern France totally disengaged from the Jewish banking business. Jews were not yet forbidden from charging interest, but government authorities would no longer enforce the payment of debts to Jews. In addition, the prohibition for rulers to not allow Jews from other domains to live on their lands became more pronounced: Wherever anyone shall find his Jew, he may legally seize him as his serf…”

During the first decades of the thirteenth century, moneylending, which had become the Jews’ main source of income, was slowly taken away from Jews, first through restrictions, and then through removal of the government’s backing. In 1235, the government even went a step further and declared that Jews should make a living from manual labor or from trade, but not anymore from interest. Although there were no sanctions set up, nonetheless, this was more than just a legal limitation of usury; this time Jews were ordered to stay away from moneylending at interest.

At the same time, the royal authorities launched another devastating campaign against the Jews, this time aimed at their religion. Before the thirteenth century, people in Christian lands knew little about the Talmud. During the 1230s, more knowledge of the Talmud became available. On the one hand, the Talmud was portrayed as evil, on the other as a source for arguments against Judaism. Even though King Louis dealt with the Talmud from both these angles (evil as well as useful for missionizing among the Jews), initially, he focused mostly on attacking the Talmud and vilifying it.

As we saw before, the attack on the Talmud was started by a convert from Judaism named Nicholas Donin. Donin came before the Pope’s court in 1236 and claimed that the Talmud – which was then still relatively unknow – was in many ways disgraceful and deserved to be banned within Christian society. We do not know exactly what Donin’s first arguments were. The earliest evidence comes from a series of letters sent by Pope Gregory IX to major religious and non-religious authorities throughout western Christendom. These letters went via the bishop of Paris and were accompanied by a special letter to the same bishop as well as to the Dominicans and Franciscans of Paris ordering them to examine the Jewish books and to burn those that were found guilty. This suggests that the Pope may have expected that such actions would only be taken in the kingdom of the religious King Louis, and that is in fact what happened.

Jewish books were confiscated, taken to Paris for examination, and eventually burned. Some years later, the Jewish leaders of royal France were able to meet with Pope Innocent IV and argued that depriving Jews from the Talmud was the same as banning Judaism altogether. The Pope agreed with this idea and decided to have the Talmud reexamined, that insulting passages should be removed, and that the rest of the Talmud should be returned to the Jews. As we saw before, this became the Church’s standard position on the Talmud. However, the order to return the Talmud to the Jews was rejected in Paris where the position was maintained that the Talmud could not be tolerated. Once again, the leaders in France – both religious and non-religious – gravitated towards the most extreme position within the Church. Although study of the Talmud did not totally disappear, the days of flourishing rabbinic creativity in northern France had come to an end. The royal attacks had not only targeted the economic basis of the northern French Jewish communities, but its spiritual foundation as well.

The religious zealousness that resulted from King Louis IX’s Christian military campaign to recover Jerusalem and the Holy Land from Islamic rule jumpstarted anti-Jewish policies that were passed by France’s royal House of Capet between 1242 and 1287. Within this period, two situations occurred in which the king showed clear evidence of his hatred towards the Jews. The first instance concerns complaints that the ban on Jewish moneylending coupled with the exile of non-complying Jews might result in Christians occupying that newly freed-up niche. When advisors brought this concern to the king, he asserted that Christian moneylending was the responsibility of the Church. However, the Jews lived under his reign, and therefore they and whatever sinfulness they might spread in his realm were his responsibility. In order to protect the purity of his soul, he had to put an end to any sin that might accumulate within France as a result of the Jews. Three significant elements of this anecdote are: the king’s sense of responsibility for the Jews’ behavior in France, King Louis’ concern for his eternal soul, and lastly, his belief that Jewish moneylending was illegal and evil. Evidently, this situation falls in line with other extreme interpretations of Church policy in northern-France (such as the removal of ‘offensive’ passages from the Talmud).

Our second evidence of Louis IX’s anti-Jewish disposition comes from Jean de Joinville, historian of the crusades who, in his Life of St. Louis gives us a shocking account of the king’s deeply ingrained attitude. Joinville describes a story told by the king about a French knight who entered into a debate at Cluny and quickly ended it by attacking the Jewish spokesman. The king’s conclusion was that the knight was right to attack the Jew since discussions between Jews and Christians might threaten Christianity. “No one who is not a very learned cleric should argue with [the Jews]. A layman, as soon as he hears the Christian faith being denigrated, should defend it only by the sword, with a good thrust in the belly…” Given Louis’s reputation as a man of peace, this report gives us an idea about his deep hatred for the Jewish people.

Later in life, Louis IX and his son Philip III continued to carry out the anti-Jewish moneylending policies that were created between 1223 to 1242. Investigations in 1247 and later revealed that Jews were still illegally practicing usury, which led to another seizure of Jewish property. Furthermore, in 1253 the king sent a letter to his officials while he was in the Middle East ordering that any Jews who refused to obey the law against usury be sent out of France. When the king returned from the Seventh Crusade in 1254, he reinforced this order. It is uncertain how many Jews left the country at this point. King Philip III continued his father’s policies against moneylending.

During this period (1242-1285), one new element of the king’s policy toward the Jews was his support for Friar Paul’s efforts to convert the Jews by persuasion. This was the same Friar Paul, also known as Pablo Christiani, who had been involved in the Barcelona Disputation. As we saw before, Friar Paul’s strategy was to argue for Christianity by using rabbinic (Jewish) teachings instead of Christian sources. Friar Paul, who previously had been supported by King James I of Aragon, now received support from King Louis XI of France to hold another disputation in Paris. There is a Hebrew record that tells us of Paul being supported by the king, of the terrifying circumstances of this type of debate, and of the deep fear among the Jewish community. The author assures us however, that no Jews were won over to Christianity.

King Philip IV was the last in medieval northern France to add tragedy to Jewish life. During his early ruling period, he simply followed the Jewish policies of the previous rulers. But late thirteenth century, certain developments convinced him to go for a massive expulsion of his Jews. The most important of these developments were increasing public hostility toward Jews, decreasing Jewish resources and economic usefulness, and a series of expulsions from several northern French principalities followed by the banishment of English Jews in 1290. In relation to the expulsions, especially the Jews’ expulsion from England, many observers mention both the strong public dislike of Jews and Jewish poverty.

In Paris 1290, a charge against the Jews for abusing sacred bread also known as host desecration had a significant impact on the Jews, as noted by both medieval and modern commentators. The story involved: a poor Christian woman who was indebted to a pawnbroker, the Jewish pawnbroker himself, his family, and the authorities of Paris. The Jew supposedly offered to relieve her from her debt in exchange for a host wafer, which she accepted. (Such a host wafer is the sacred bread used during the Christian ritual. And during this ritual, the host is believed to become Jesus’ body.) The woman agreed to give the host, and the Jew supposedly tried to torture it (the body of christ), but Christians discovered the crime. The Jew was sentenced to death by a religious court and royal officials burned him.

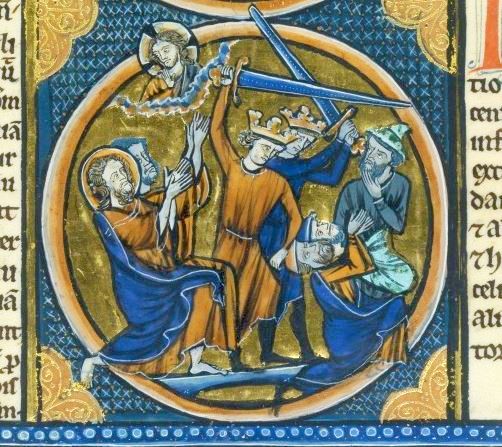

The host allegation was another version of the twelfth century portrayal of Jews as the enemy of Christ. This sense of Jewish hatred led to the concept of Jewish murder of innocent children. These Christian victims were identified with the innocent Jesus who suffered at the hands of wicked Jews and were memorialized as martyrs. According to Thomas of Monmouth, such ritual murders were carried out through crucifixion. Later, the idea evolved and became connected with elements of Jewish ritual, either with ancient sacrifices or with contemporary Passover rituals. The host desecration was mainly a spinoff of this theme which reflected the growing importance that the Church gave to the doctrine of transubstantiation (i.e. that a consecrated wafer – or host – changed into the actual body of Christ.

It is important to see how the attitude towards anti-Jewish allegations of the French authorities – both of Church and state – changed over time. We saw that during the 1170s, the archbishop of Sens had intervened on behalf of the Jews of Blois who were executed by his brother, Count Theobald, on a ritual murder charge. In addition, King Louis VII had assured a delegation of Jewish leaders that a ritual murder charge was brought up in two of his towns and that he had rejected both allegations. He assured them that this would be his policy in the future. In contrast, by 1290, the bishop of Paris and the king of France accepted the new allegation, condemned the alleged Jewish offender, and began the creation of a monument for the miracles associated with the allegedly stolen wafer, which increased public acceptance of such charges by introducing a ritualized commemoration of the alleged crime.

It is not clear to what extent the 1290 incident contributed to the king’s decision to expel the Jews. The king was probably influenced by a combination of the factors we already saw as well as by his anti-Jewish tendencies evident from his behavior in 1290. In any case, the Jews were ordered to leave royal France in 1306. This was by far the most devastating expulsion that the Jews of medieval western Christendom had suffered yet. We already saw several previous banishments such as the expulsion in 1182 from the French royal domain under Philip Augustus. However, none of the previous expulsions affected this many Jews, nor had it ever been so hard for the banished Jews to find a place of refuge.

Philip IV was eager to make this the most profitable anti-Jewish operation in the history of the French kingdom. While the Jews were allowed to take their moveable goods with them, their real estate fell to the crown. A governmental department was set up to sell off Jewish property and make the highest profits. More significantly, Jewish business records were confiscated, and royal officials became collectors of money owed to Jews, be it with certain reductions of the outstanding debt in order to prevent the appearance that the king would benefit from interest. This last point (reduction of debt) did not work well. There is ample evidence that royal officials misbehaved and forced the debtors to pay more than they had to. In short, royal profits were substantial, certainly much more than profits from earlier expiations, confiscations, and bribes.

The difficulty to realize maximal profits from the expulsion compelled Philip IV’s heir, Louis X, to permit several Jews back into the French kingdom in 1315. The proclamation of Jewish return shows an interesting reasoning. It begins with a long justification of the reversal of Philip IV’s expulsion. Factors mentioned include biblical teachings including the divine promise of Jewish conversion, doctrines of the Roman Catholic Church that Jews should present a constant memory of Jesus’ suffering, and that Jews will ultimately embrace the truth of Christianity, the legacy of St. Louis who had first expelled the Jews and then invited them back in, and (rather implausible) pressure from the people.

The invitation to return came with many conditions that were intended to restrict Jewish behavior. Of these we shall only mention a few. The Talmud remained forbidden, and Jews were not allowed to dispute religious matters with Christians. Moreover, Jews were to wear a special badge – already introduced in the thirteenth century – to make them recognizable. Control of the Jews was firmly established: “No other lord in our kingdom (…) may hold in his land Jews of another lord…” By exception, only the king may take over Jews ‘belonging’ to another.

The stipulations and conditions under which Jews could reenter France mostly focused on the Jews’ economic activities. Many of the previous prohibitions from the thirteenth century were reinstituted. One rule, initially instituted by Louis IX, stated that Jews must “live by the labor of their hands, or they must trade in good and reliable merchandise.” This implied that lending against interest was forbidden, be it merely forbidden in theory while permitted in practice. Another rule was that “no one may be forced (…) to pay interest of any [amount] to a Jew”. A third law, initially instituted in 1206 by Philip Augustus, states that “since the Jews must work (…) with their hands or [else] must trade…”, they are forbidden from lending against interest. However paradoxically, if it should happen anyway, they may only charge two pence interest per pound per week. In addition, lending could no longer take place with governmental documents, and could only be done against pledges. This 1315 legal document with all its contradictions provides insight into the evolving French anti-interest policy that influenced the region for decades to come.

Returning Jews, who previously owned valuable property, encountered steep provisions back in France. The most profound was that Jews “may recover and hold a third, while we [the king] hold two-thirds of the debts that had been owed them prior to their expulsion”. This stipulation may well reveal the main reason for allowing Jews back into France. Returning Jews would track down those who had owed them money prior to 1306, and while doing so (through the ⅓-⅔ provision), help fill the coffers of the king.

Any Jewish property that was resold after 1306 would remain in the hands of its Christian buyers, with some exclusion to Jewish public spaces. Jewish public spaces that were not yet resold were returned. However, if they were already resold, the Jews had to pay the price for which they had been sold. Large and otherwise important buildings were not to given back. The following sounds nicer than it is: “If perchance they are unable to recover their synagogues and cemeteries for good reason, we shall see that they receive [other] sufficient buildings and ground for a suitable price.” Payment is spelled all over these stipulations.

While some Jews did return, the time of Jewish creativity was over. Individuals and families did resettle, and some communities reemerged, but without the former vibrancy and creativity that had characterized Jewish life in northern France during the eleventh through the thirteenth century. When a final expulsion was decreed in 1394, the Jewish community broke up once again. But it had little impact on northern-European Jewish culture as a whole. The Jewish community that was dismantled in 1394 was just a mere shadow of its former self.

Though the anti-Jewish sentiments that went along with the First Crusade were based on the New Testament’s narrative of the Jews’ murdering of Jesus and on calls for Christian revenge, by the middle of the twelfth century, the dominant perception of Jews was that they were enemies of Christianity here-and-now, and that they were always inclined to bring harm to Christian society. This lead the militant and influential abbot Peter the Venerable of Cluny to urge the king of France to let the Jews pay for part of the expenses of the Second Crusade because of their never-ending hatred of Christianity and their blasphemy against the Christian faith.

The most dangerous outgrowth of this notion of ongoing Jewish hatred and hostility was the belief that Jews regularly murdered Christian neighbors in secret. In most of such cases, the alleged victim was a (defenseless and innocent) child. Such murder accusations came up all over northern Europe during the mid-twelfth century. This quickly grew into a conviction that these murders were committed out of religious motives and that the victims were therefore Christian martyrs. This further evolved into allegations of ritualized murder such as claims that killings were done by crucifixion or as part of a renewed Jewish sacrificial cult.

In 1171, an unusual case of Jewish murder accusation took place in the town of Blois. The incident in Blois was unusual in several ways: Firstly, there was never a Christian corpse. Secondly, the local ruler, Count Theobald of Blois, accepted the allegation without evidence and ordered a so-called ‘trial by ordeal’. A trial by ordeal meant putting someone through a test, such as throwing the accused in water to see if he or she would float or sink. Such a superstitious way of testing if someone was guilty was quite common at the time. Based on this ‘ordeal’, the Jews were convicted and more than thirty of them were executed. The incident caused deep fear among the Jews of northern France who were afraid that this conviction would further fuel the idea that Jews were murderous people.

To counter the threat, the Jews of northern France organized a campaign by carefully investigating all events that had taken place in Blois in order to disprove the accusations and to persuade the northern French authorities to dismiss the charge. Both Count Henry of Champagne – the brother of Count Theobald – and King Louis VII – his brother-in-law – rejected the murder allegation. During a meeting with the Jewish leaders, the king distanced himself from Count Theobald’s actions and reassured his frightened Jews: “Be aware, all you Jews of my land, that I harbor no such suspicions. Even if a body be discovered in the city or the countryside, I shall say nothing to the Jews in that regard. Therefore, be not frightened over this matter.” This message was distributed to royal officials throughout the king’s domain by a written charter.

The statement of the king after the events of Blois shows the general position of the ruling class of northern class of northern France. Except for the incident in Rouen, the Jews of northern France seem to have been well protected by their lords during the First Crusade. This in stark contrast with the loss of Jewish lives further eastward in the Rhineland. At the beginning of the Second Crusade, the authorities of both Church and state, as well as the Jews themselves, were all very much aware of the grave dangers for the Jews that went hand-in-hand with crusading. The important spiritual leader behind the Second Crusade, Bernard of Clairvaux, while he was campaigning for the Crusade and recruiting Christian warriors, also warned against inflicting violence upon the Jews. As a result, Ephraim of Bonn, who documented the events of the Second Crusade, had little violence to report, even for areas in the Rhineland.

Ephraim describes one frightening incident in which the life of Rabbi Jacob ben Meir, a Jewish leader in northern France, was threatened and then saved. After describing the incident, Ephraim adds: “In the rest of the communities in France, we have not heard of anyone killed or forcibly converted. However, the Jews lost much of their wealth, for the king of France commanded: ‘All who volunteer to go to Jerusalem shall have their debts forgiven if they are indebted to the Jews.’ Since most of the Jews’ loans are by charter [i.e. with no security deposit], they lost their monies.” Even though there were some allegations of Jewish murder during the second half of the twelfth century, it seems that the rulers of northern France effectively protected the Jews; there are no reports of the loss of Jewish lives by angry mobs.

However, there were two notable occasions where rulers of northern France turned against the Jews. For example, we already saw the incident of Blois in 1171 where Count Theobald of Blois was responsible for the death of more than thirty Jews. One of the Hebrew letters mentioned above suggests the complicated combination of romantic and political circumstances behind the court of Blois’ unusual actions of killing the Jews. There was another case in which Philip Augustus, the young king of France at the time, initiated an assault that killed more than eighty Jews living in an area next to the territory belonging to the French royalty. The attack was based on assumptions of Jewish murder and the notion that King Philip Augustus needed to set matters straight. There also may have been political motivations. In any case, the actions of Count Theobald of Blois and King Philip Augusts were exceptions to the rules. For the most part, the rulers of northern France protected their Jews effectively throughout the stormy twelfth century.

Even as a minority group, the Jews of northern France were able to increasingly flourish in their spiritual endeavors throughout the eleventh and twelfth centuries. The heart of Jewish organizational life lay in the way the local community were organized. We lack details, but it is clear that the local Jewish communities of northern France developed effective systems of taxation and law enforcement, already during the eleventh century.

During the twelfth century, the Jews of Northern France realized that they needed to organize and defend themselves more efficiently. The Blois incident shows that the Jews of northern France were able to organize themselves on a broader level than just locally and thereby achieve some successes through negotiating with the leaders of the Church and with local rulers. One important figure heavily involved in this was Rabbi Jacob ben Meir who lived in Ramerupt, in the county of Champagne. He worked together with the leaders of the Jewish communities of Troyes in Champagne and of Paris and Orleans which were in the domain of the king. Together they approached the king, the counts of Champagne and Blois, and the archbishop of Sens. Developing such a new level of Jewish cooperation turned out to be crucial to Jewish survival in twelfth century northern France which was on the brink changing toward centralization.

Cooperation within the Jewish community was more than just defensive. Rabbi Jacob ben Meir and his brother Rabbi Samuel ben Meir were key players in bringing together representatives from different Jewish communities to set up regulations that helped the Jewish leaders deal with the challenges of the twelfth century. Some of these ordinances that were widely accepted across northern France and beyond have survived. Even though these regulations were in response to issues that were relatively minor compared to the events in Blois, these ordinances show the broad cooperation among Jewish leaders in twelfth century northern France and the important role that Jacob and Samuel ben Meir played. The Jews knew that northern France was making a tremendous change towards centralization and had to take measures to adapt to this big change.

The same creative energy that is evident from success in Jewish business and community organization can be seen in northern French Jewish culture. The creativity found within Jewish culture in eleventh and twelfth century northern France was stimulated by the general environment. While it is relatively easy to show the impact that the medieval Muslim society had on Jewish cultural activity where Muslims and Jews shared a written language and easily understood each other’s writings, in the world of western Christendom where people spoke Romance languages and Latin was the language of literature, it is much more difficult to understand the connections and to recognize the various influences. However, in some areas of southern Europe, such as Italy, it is possible to discern cultural influences, for instance by looking at the poetry of Immanuel of Rome and his innovative style of poetry. For the Jewish cultural creativity in northern Europe which expressed itself in traditional Jewish ways, it is impossible to identify exactly what the impact of the general society was and how it impacted Jewish culture. All we can do is argue that the richness of Jewish creativity must have some sort of relationship with the vibrant surrounding society, and we can point at some parallels in both cultures.

During the eleventh century, a Jewish man named Rabbi Solomon ben Isaac was to become a pioneer in this cluster of young Jewish communities. A native from the town of Troyes, in Champagne (now France), he made the decision to immerse himself in Jewish studies in the most flourishing center of Jewish culture of northern Europe. He traveled eastward to study in the Rhineland and eventually returned to Champagne to share what he had learned. He is now known as Rashi. Rashi was extremely productive; he composed two large commentaries, one on the Bible and one on the Babylonian Talmud. Both works became extremely influential in consequent Jewish life. Possibly the most remarkable about impressive his works is that they were created at such an early stage of a young, emerging community.

Besides for his own influential work, Rashi is also recognized for initiating new trends in talmudic and biblical commentary. These new tendencies would continue for more than a century after his death. His style of talmudic commentary would dominate the study of Talmud from the twelfth through the twenty-first century. The specifics of his commentary style will be discussed later in this book. For now, it is enough to state that the young northern-French Jewish communities were not only innovative in areas of economy and community organization, but at least as much in areas of Jewish cultural and religious life.

Jewish life and creativity in twelfth-century northern France took place amid a dynamic Christian society with lots of political diversity. But that was going to change. During the thirteenth century, northern France became united under the rule of the Capetian kings, who ruled from their capital Paris over ever-larger territories in the north and later also in the south. This change towards a more central government initially was a blessing for the Jews of northern France who had been organized as independent communities in each of the territories they were located. However, centralization would turn out to have major drawbacks. The fate of the Jews now rested upon one ruler. When, in the twelfth century, several rulers in northern France expelled the Jews from their territory, these refugees could easily find new homes in other domains, not too far away and without much economic detriment. But when King Philip the Fair expelled his Jews in the early fourteenth century, a much bigger territory was part of the royal domain, and Jews had to travel much further to find refuge in vastly different societies.

During the rule of King Philip Augustus (1172-1223), northern France and Jewish communities across northern France experienced new developments and concentration of authority. At the beginning of King Philip's reign, he had limited power and resources. In contrast, at the time of his death, he left behind a much larger kingdom, great wealth, and prestige. What King Philip's view and goals were on the Jews is not clear; his policies towards them shifted in unpredictable ways. At the end of the day, King Philip's centralization of authority and his Jewish policies would contribute to the downfall of Jewish communities in Northern France during the thirteenth century.

The poor circumstances of King Philip’s early years on the throne led him to a series of anti-Jewish measurement. In a first move, King Philip seized a wide range of Jewish goods which the Jews could then ‘ransom’ (buy back). This confiscation perhaps indicates how well-off the northern French Jewish communities were economically, as they were perceived as a potential source of financial resources. The monarchy repeated such grabs several times throughout the thirteenth century. A second royal measurement concerned moneylending, a growing Jewish specialization which increasingly evoked hostility. King Philip ordered that debts owed to Jews were forgiven and one-fifth of the debt was to be paid to the royal treasury. In 1182, King Philip banished all Jews from the royal domain, thereby taking possession of Jewish property, while synagogues were handed over to the Church.

While Rigord, in his biography of King Philip, tries to justify all these measurements as reactions to Jewish crimes flowing from Philip’s responsibility as a “most Christian king”, what all these moves had in common was financial gain, catering to the wishes of the Church, and smartly tapping into the sentiments of the general public. In each of these moves, the impoverished monarchy gained significant financial resources. Forgiveness of debt and the transfer of synagogues gave King Philip greater support of the Church. The royal biographer Rigord describes very well how King Philip, through his actions gained greater support. He sees the king’s anti-Jewish moves as among the major achievements of Philip’s earlier years on the throne. Forgiveness of debt to Jews certainly was a popular measurement for those who were in debt. Paying only twenty percent to the treasury instead must have seemed like a good deal. Finally, the expulsion of the Jews was probably popular among many Christians. The same may have been the case when the king attacked the Jewish community of a neighboring territory.

Rigord was delighted about the young king’s anti-Jewish moves but upset when the king decided to readmit the Jews to France in 1198. The change of royal policy was inspired in part because of Jews being on the move after anti-Jewish riots that were sparked by the preaching of Fulk of Neuilly. With Jews wandering from place to place, King Philip decided to attract some of them back to his kingdom, thereby stimulating the economy through Jewish money lending and taxing opportunities associated with Jewish banking.

During the later years of King Philip Augustus, which lasted until 1223, there were three significant developments that affected to the Jews. The first was the quick expansion of the king’s territory, including the removal of the Angevin kingdom, which resulted in more Jews living under his control, protection, and taxation. The king’s influence was even felt in areas that remained independent. King Philip Augustus established new policies for Jewish moneylending which became standard practice in most of northern France, even in independent domains. For instance, in 1206, a new set of rules regarding Jewish moneylending was implemented in the king’s domain and, at the same time, in two other important territories. As a result, Jews could not simply move from one are to another to avoid these new limitations. Philip Augustus used the Jews as a tool to increase his power.

The second development after was stricter control over the Jews, meant to exploit Jewish wealth more effectively. The outcome would eventually be a drastic restriction of Jewish movement and a lowering of the Jews’ status. As we saw, before this point, it had been easy and quite common for Jews to move from place to place. Even during expulsions in 1182 and 1190, Jews were able to cope rather well because they could find refuge in nearby areas. Once Philip readmitted Jews to his domain, he took full control over them. One way he achieved this through a treaty with the count of Champagne where many northern-French Jews lived. The king promised: “We shall retain in our land none of the Jews of (…) Theobald, count of Troyes, unless with the consent of that count.” At the same time, the count made the same promise with respect to the Jews of the king. Each signatory of the treaty was now guaranteed full control of his Jews, and it became extremely hard for Jews to move. After conquering Normandy, Philip made sure to secure his control over its Jews as well. Jews were forced to give guarantee deposits for their continued presence and acceptance of royal control. The result of the king’s strategies was that the Jews became restricted in their movements and more effectively exploited.

The history of Jews after 1198, under Philip Augustus’s reign, marked a significant event that shaped their lives tremendously. In 1210, Jews all over northern France were arrested and their possessions taken away. To get it back, the Jews had to pay exorbitant amounts of money, which put a huge burden on them for years to come. Again, firmer control over the Jews, prevented them from seeking any relief from this crushing abuse.

While the king’s greed lay at the root of the new policy of controlling Jewish movement and occasionally taking away portions of Jewish wealth, there was a third, opposite trend in Philip Augustus’s policies which can be only understood in relation to his commitment to the Church and the need to appease its leaders. As previously noticed, the Church’s concern with Jewish moneylending had increased during the second half of the twelfth century. This concern expressed itself in several ways. For some Church leaders, Jewish moneylending resulted in abuses that had to be addressed and eliminated; for others, Jewish moneylending was principally wrong – Deuteronomy 23:21 could not be read to allow Jews to take interest from Christians. In the court of the Pope, it was the former view that dominated, leading among other things to the edicts of the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215 that prohibited excessive Jewish usury. Excessive seems to have been defined as an interest rate of more than twenty percent per year. As was often the case, the leaders of the Church in northern France leaned towards the more extreme position. We already saw the campaign of Fulk of Neuilly at the end of the twelfth century to eradicate Jewish moneylending altogether, inspired by the idea that Jewish taking of interest was essentially illegal.

Already in 1205, the powerful Pope Innocent III sent a strong letter of rebuke to King Philip Augustus. The first and most striking of the Pope’s complaints concerned Jewish moneylending: “… in the French kingdom, the Jews have become so disrespectful that by means of their dangerous usury, through which they not only charge interest, but even interest upon interest, they take possession of Church goods and Christian possessions. What the prophet said about the Jews is being fulfilled among the Christians: ‘Our heritage has been turned over to strangers, our houses to foreigners.’” The Pope’s complaint does not portray Jewish interest taking as sinful in and of itself; the focus is on the unwelcome consequences of Jewish usury – Jewish confiscation of church vessels and Christian property. Some concessions to the demands of the Church had to be made, and in fact it was.

King Philip Augustus decreed a chain of restrictions on Jewish money lending which severely limited Jewish income from banking. Two powerful figures, the countess of Champagne and the lord of Dampierre, joined forces with the crown and issued an edict in 1206. The most important stipulation of this edict was a maximum interest rate of twenty percent per year, a decree in anticipation of the Fourth Lateran Council (an important assembly of the Catholic Church, held in 1215, that would issue numerous anti-Jewish measurements) . Another stipulation was a prohibition on Jews from collecting their loans within the first year because of an issue the Pope had with compound interest. Towards the end of his rule, in 1219, King Philip Augustus once again addressed the Church’s concerns with Jews and money lending and the consequences it brought to society. In a new set of measurements, King Philip dealt with debts that weighed down the poor people of France as well as Church institutions. are struggling to preserve their society while being indebted to the Jews. These new laws were meant to protect these rather defenseless sectors of French society.

The long rule of Philip Augustus would prove to be a turning point in the development of royal France and for the Jews as well. While his policies show elements of instability, the most severe concerns – enhanced control of the Jews, exploitation of their wealth, and severe limitations of the moneylending business – foreshadowed what was to come. The long and effective rule of Philip Augustus would prove to be the beginning of the decline of Jewish fate in northern France. However, there was no way for the Jews living under his rule to foresee that.

The historian William Chester Jordan describes three phases of the decline that Philip Augustus set in motion: (1) the brief reign of Louis VIII and early years of Louis IX (1223-1242); (2) the mature years of Louis IX and reign of Philip III (1242-1285); (3) the reign of Philip IV and the expulsion (1285-1306). The Jews were readmitted to royal France in 1315, but the real history of Jewish society in medieval northern France really ended with the expulsion of 1306.

In the first of these stages, the often-fluctuating policies introduced under Philip Augustus become more consistent. The two opposing trends of both royal exploitation of Jewish money lending and simultaneously opposing it went hand in hand. At the beginning of Louis VIII’s reign, in 1223, the king ordered that all debts owed to Jews would no longer bear interest and were to be paid off over three years to the royal treasury. This was another confiscation of Jewish wealth while the treasury did not benefit from interest. What is more significant in the long run was a rule that Jews were no longer allowed to seal their debts, which collapsed their system of banking. Jewish lending in northern France had been conducted with the support of local rulers and royal authorities, but this support was now removed. The increasingly religions rulers of northern France wanted to distance themselves completely from Jewish moneylending. These laws were initiated by twenty-six northern-French rulers and came with increased control over the Jews. These rulers were not allowed anymore to admit Jews from other domains. In other words, Jews were no longer able to flee from one area to another.

Seven years later, during the early years of King Louis IX, the French rulers sharpened the trend of 1223 even more. “We (…) shall henceforth enforce no contracted debts to be repaid to the Jews.” Hereby, the king and the local rulers of northern France totally disengaged from the Jewish banking business. Jews were not yet forbidden from charging interest, but government authorities would no longer enforce the payment of debts to Jews. In addition, the prohibition for rulers to not allow Jews from other domains to live on their lands became more pronounced: Wherever anyone shall find his Jew, he may legally seize him as his serf…”

During the first decades of the thirteenth century, moneylending, which had become the Jews’ main source of income, was slowly taken away from Jews, first through restrictions, and then through removal of the government’s backing. In 1235, the government even went a step further and declared that Jews should make a living from manual labor or from trade, but not anymore from interest. Although there were no sanctions set up, nonetheless, this was more than just a legal limitation of usury; this time Jews were ordered to stay away from moneylending at interest.

At the same time, the royal authorities launched another devastating campaign against the Jews, this time aimed at their religion. Before the thirteenth century, people in Christian lands knew little about the Talmud. During the 1230s, more knowledge of the Talmud became available. On the one hand, the Talmud was portrayed as evil, on the other as a source for arguments against Judaism. Even though King Louis dealt with the Talmud from both these angles (evil as well as useful for missionizing among the Jews), initially, he focused mostly on attacking the Talmud and vilifying it.

As we saw before, the attack on the Talmud was started by a convert from Judaism named Nicholas Donin. Donin came before the Pope’s court in 1236 and claimed that the Talmud – which was then still relatively unknow – was in many ways disgraceful and deserved to be banned within Christian society. We do not know exactly what Donin’s first arguments were. The earliest evidence comes from a series of letters sent by Pope Gregory IX to major religious and non-religious authorities throughout western Christendom. These letters went via the bishop of Paris and were accompanied by a special letter to the same bishop as well as to the Dominicans and Franciscans of Paris ordering them to examine the Jewish books and to burn those that were found guilty. This suggests that the Pope may have expected that such actions would only be taken in the kingdom of the religious King Louis, and that is in fact what happened.

Jewish books were confiscated, taken to Paris for examination, and eventually burned. Some years later, the Jewish leaders of royal France were able to meet with Pope Innocent IV and argued that depriving Jews from the Talmud was the same as banning Judaism altogether. The Pope agreed with this idea and decided to have the Talmud reexamined, that insulting passages should be removed, and that the rest of the Talmud should be returned to the Jews. As we saw before, this became the Church’s standard position on the Talmud. However, the order to return the Talmud to the Jews was rejected in Paris where the position was maintained that the Talmud could not be tolerated. Once again, the leaders in France – both religious and non-religious – gravitated towards the most extreme position within the Church. Although study of the Talmud did not totally disappear, the days of flourishing rabbinic creativity in northern France had come to an end. The royal attacks had not only targeted the economic basis of the northern French Jewish communities, but its spiritual foundation as well.

The religious zealousness that resulted from King Louis IX’s Christian military campaign to recover Jerusalem and the Holy Land from Islamic rule jumpstarted anti-Jewish policies that were passed by France’s royal House of Capet between 1242 and 1287. Within this period, two situations occurred in which the king showed clear evidence of his hatred towards the Jews. The first instance concerns complaints that the ban on Jewish moneylending coupled with the exile of non-complying Jews might result in Christians occupying that newly freed-up niche. When advisors brought this concern to the king, he asserted that Christian moneylending was the responsibility of the Church. However, the Jews lived under his reign, and therefore they and whatever sinfulness they might spread in his realm were his responsibility. In order to protect the purity of his soul, he had to put an end to any sin that might accumulate within France as a result of the Jews. Three significant elements of this anecdote are: the king’s sense of responsibility for the Jews’ behavior in France, King Louis’ concern for his eternal soul, and lastly, his belief that Jewish moneylending was illegal and evil. Evidently, this situation falls in line with other extreme interpretations of Church policy in northern-France (such as the removal of ‘offensive’ passages from the Talmud).

Our second evidence of Louis IX’s anti-Jewish disposition comes from Jean de Joinville, historian of the crusades who, in his Life of St. Louis gives us a shocking account of the king’s deeply ingrained attitude. Joinville describes a story told by the king about a French knight who entered into a debate at Cluny and quickly ended it by attacking the Jewish spokesman. The king’s conclusion was that the knight was right to attack the Jew since discussions between Jews and Christians might threaten Christianity. “No one who is not a very learned cleric should argue with [the Jews]. A layman, as soon as he hears the Christian faith being denigrated, should defend it only by the sword, with a good thrust in the belly…” Given Louis’s reputation as a man of peace, this report gives us an idea about his deep hatred for the Jewish people.

Later in life, Louis IX and his son Philip III continued to carry out the anti-Jewish moneylending policies that were created between 1223 to 1242. Investigations in 1247 and later revealed that Jews were still illegally practicing usury, which led to another seizure of Jewish property. Furthermore, in 1253 the king sent a letter to his officials while he was in the Middle East ordering that any Jews who refused to obey the law against usury be sent out of France. When the king returned from the Seventh Crusade in 1254, he reinforced this order. It is uncertain how many Jews left the country at this point. King Philip III continued his father’s policies against moneylending.

During this period (1242-1285), one new element of the king’s policy toward the Jews was his support for Friar Paul’s efforts to convert the Jews by persuasion. This was the same Friar Paul, also known as Pablo Christiani, who had been involved in the Barcelona Disputation. As we saw before, Friar Paul’s strategy was to argue for Christianity by using rabbinic (Jewish) teachings instead of Christian sources. Friar Paul, who previously had been supported by King James I of Aragon, now received support from King Louis XI of France to hold another disputation in Paris. There is a Hebrew record that tells us of Paul being supported by the king, of the terrifying circumstances of this type of debate, and of the deep fear among the Jewish community. The author assures us however, that no Jews were won over to Christianity.

King Philip IV was the last in medieval northern France to add tragedy to Jewish life. During his early ruling period, he simply followed the Jewish policies of the previous rulers. But late thirteenth century, certain developments convinced him to go for a massive expulsion of his Jews. The most important of these developments were increasing public hostility toward Jews, decreasing Jewish resources and economic usefulness, and a series of expulsions from several northern French principalities followed by the banishment of English Jews in 1290. In relation to the expulsions, especially the Jews’ expulsion from England, many observers mention both the strong public dislike of Jews and Jewish poverty.

In Paris 1290, a charge against the Jews for abusing sacred bread also known as host desecration had a significant impact on the Jews, as noted by both medieval and modern commentators. The story involved: a poor Christian woman who was indebted to a pawnbroker, the Jewish pawnbroker himself, his family, and the authorities of Paris. The Jew supposedly offered to relieve her from her debt in exchange for a host wafer, which she accepted. (Such a host wafer is the sacred bread used during the Christian ritual. And during this ritual, the host is believed to become Jesus’ body.) The woman agreed to give the host, and the Jew supposedly tried to torture it (the body of christ), but Christians discovered the crime. The Jew was sentenced to death by a religious court and royal officials burned him.

The host allegation was another version of the twelfth century portrayal of Jews as the enemy of Christ. This sense of Jewish hatred led to the concept of Jewish murder of innocent children. These Christian victims were identified with the innocent Jesus who suffered at the hands of wicked Jews and were memorialized as martyrs. According to Thomas of Monmouth, such ritual murders were carried out through crucifixion. Later, the idea evolved and became connected with elements of Jewish ritual, either with ancient sacrifices or with contemporary Passover rituals. The host desecration was mainly a spinoff of this theme which reflected the growing importance that the Church gave to the doctrine of transubstantiation (i.e. that a consecrated wafer – or host – changed into the actual body of Christ.

It is important to see how the attitude towards anti-Jewish allegations of the French authorities – both of Church and state – changed over time. We saw that during the 1170s, the archbishop of Sens had intervened on behalf of the Jews of Blois who were executed by his brother, Count Theobald, on a ritual murder charge. In addition, King Louis VII had assured a delegation of Jewish leaders that a ritual murder charge was brought up in two of his towns and that he had rejected both allegations. He assured them that this would be his policy in the future. In contrast, by 1290, the bishop of Paris and the king of France accepted the new allegation, condemned the alleged Jewish offender, and began the creation of a monument for the miracles associated with the allegedly stolen wafer, which increased public acceptance of such charges by introducing a ritualized commemoration of the alleged crime.

It is not clear to what extent the 1290 incident contributed to the king’s decision to expel the Jews. The king was probably influenced by a combination of the factors we already saw as well as by his anti-Jewish tendencies evident from his behavior in 1290. In any case, the Jews were ordered to leave royal France in 1306. This was by far the most devastating expulsion that the Jews of medieval western Christendom had suffered yet. We already saw several previous banishments such as the expulsion in 1182 from the French royal domain under Philip Augustus. However, none of the previous expulsions affected this many Jews, nor had it ever been so hard for the banished Jews to find a place of refuge.

Philip IV was eager to make this the most profitable anti-Jewish operation in the history of the French kingdom. While the Jews were allowed to take their moveable goods with them, their real estate fell to the crown. A governmental department was set up to sell off Jewish property and make the highest profits. More significantly, Jewish business records were confiscated, and royal officials became collectors of money owed to Jews, be it with certain reductions of the outstanding debt in order to prevent the appearance that the king would benefit from interest. This last point (reduction of debt) did not work well. There is ample evidence that royal officials misbehaved and forced the debtors to pay more than they had to. In short, royal profits were substantial, certainly much more than profits from earlier expiations, confiscations, and bribes.

The difficulty to realize maximal profits from the expulsion compelled Philip IV’s heir, Louis X, to permit several Jews back into the French kingdom in 1315. The proclamation of Jewish return shows an interesting reasoning. It begins with a long justification of the reversal of Philip IV’s expulsion. Factors mentioned include biblical teachings including the divine promise of Jewish conversion, doctrines of the Roman Catholic Church that Jews should present a constant memory of Jesus’ suffering, and that Jews will ultimately embrace the truth of Christianity, the legacy of St. Louis who had first expelled the Jews and then invited them back in, and (rather implausible) pressure from the people.

The invitation to return came with many conditions that were intended to restrict Jewish behavior. Of these we shall only mention a few. The Talmud remained forbidden, and Jews were not allowed to dispute religious matters with Christians. Moreover, Jews were to wear a special badge – already introduced in the thirteenth century – to make them recognizable. Control of the Jews was firmly established: “No other lord in our kingdom (…) may hold in his land Jews of another lord…” By exception, only the king may take over Jews ‘belonging’ to another.

The stipulations and conditions under which Jews could reenter France mostly focused on the Jews’ economic activities. Many of the previous prohibitions from the thirteenth century were reinstituted. One rule, initially instituted by Louis IX, stated that Jews must “live by the labor of their hands, or they must trade in good and reliable merchandise.” This implied that lending against interest was forbidden, be it merely forbidden in theory while permitted in practice. Another rule was that “no one may be forced (…) to pay interest of any [amount] to a Jew”. A third law, initially instituted in 1206 by Philip Augustus, states that “since the Jews must work (…) with their hands or [else] must trade…”, they are forbidden from lending against interest. However paradoxically, if it should happen anyway, they may only charge two pence interest per pound per week. In addition, lending could no longer take place with governmental documents, and could only be done against pledges. This 1315 legal document with all its contradictions provides insight into the evolving French anti-interest policy that influenced the region for decades to come.

Returning Jews, who previously owned valuable property, encountered steep provisions back in France. The most profound was that Jews “may recover and hold a third, while we [the king] hold two-thirds of the debts that had been owed them prior to their expulsion”. This stipulation may well reveal the main reason for allowing Jews back into France. Returning Jews would track down those who had owed them money prior to 1306, and while doing so (through the ⅓-⅔ provision), help fill the coffers of the king.

Any Jewish property that was resold after 1306 would remain in the hands of its Christian buyers, with some exclusion to Jewish public spaces. Jewish public spaces that were not yet resold were returned. However, if they were already resold, the Jews had to pay the price for which they had been sold. Large and otherwise important buildings were not to given back. The following sounds nicer than it is: “If perchance they are unable to recover their synagogues and cemeteries for good reason, we shall see that they receive [other] sufficient buildings and ground for a suitable price.” Payment is spelled all over these stipulations.