|

|

Pesach/Passover in Uganda

|

|

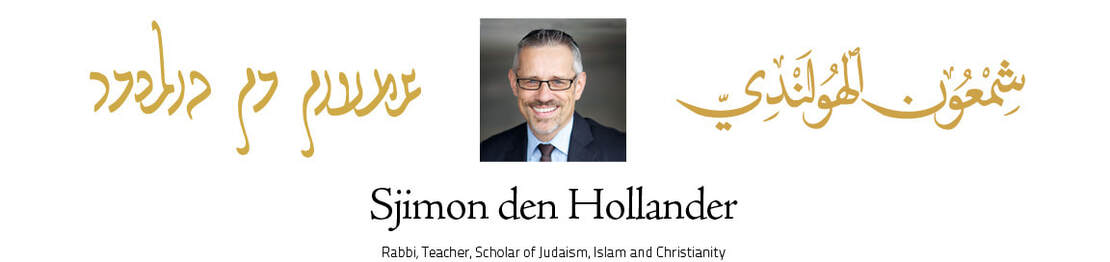

- Personal

-

JUDAISM

- Judaism - Introduction

-

Jewish History

>

- Paleo Hebrew

- The Pentateuch

- Stories of Creation

- Stories of the Flood

- J and E compared

- Priestly Writings

- Prophets of Israel and Judah

- Biblical Poetry

- Hellenism and the Septuagint

- Flavius Josephus

- The Dead Sea Scrolls

- Midrash

- Oral Torah and Talmud

- Origins of Christian Anti-Jewish Attitudes

- Byzantine Jews Before the Advent of Islam

- Yannai

- Jews Under Islam

- Byzantine Jews After the Advent of Islam

- Qara'ites

- Saadia Gaon

- Saadia Gaon's Poem Telóf Tèlef

- Salmón ben Yeruḥám

- Hasdai ibn Shaprut

- Yoséf ibn Abiṭúr

- Andalusian Poetry

- Samuel haNagîd and Ibn Gabirol

- Christian-Jewish Polemics

- The Crusades and Maoz Tzur

- Rashi

- The Tosafists

- Yehuda haLevi

- Ritual Murder and Blood Libel

- The Ḥasidé Ashkenaz

- Toledot Yeshu

- Moses Maimonides, Philosopher

- Moses Maimonides, Rabbi, Leader, Physician

- Abraham Maimonides

- Maimonidean Controversies

- Host Desecration Libels

- The Barcelona Disputation

- Qabbala and the Zohar

- The Cairo Geniza

- The New Sephardi Identity

- David Reubeni and Shelomo Molkho

- Shabbatai Tzevi

- Da Costa and Spinoza

- Yiddish Texts

- Ḥasidism

- The Jewish Enlightenment

- Modern Jewish Thinkers

- Jewish Thought >

- Jewish Law >

- Scripture

-

Liturgy

- Daily Prayers

- Shabbat >

- Rosh Ḥodesh (New Moon)

- Shabbat Rosh Ḥodesh >

- Shabbat Zakhor

- Purim

- Passover/Pesach >

- Omer Counting

- Shabu'oth >

- Tish'a beAbh Evening Service

- The Month of Elul

- Rosh haShana (New Year) >

- Shabbat Teshubá

- Yom Kippur

- Sukkot (Festival of Booths) >

- Sheminí ʻAṣèreth

- Simḥàt Torah

- Ḥanukka >

- CHRISTIANITY

- ISLAM

- (DIS)COURSES

-

OTHER LANGUAGES

- UGANDA

- Contact

- Personal

-

JUDAISM

- Judaism - Introduction

-

Jewish History

>

- Paleo Hebrew

- The Pentateuch

- Stories of Creation

- Stories of the Flood

- J and E compared

- Priestly Writings

- Prophets of Israel and Judah

- Biblical Poetry

- Hellenism and the Septuagint

- Flavius Josephus

- The Dead Sea Scrolls

- Midrash

- Oral Torah and Talmud

- Origins of Christian Anti-Jewish Attitudes

- Byzantine Jews Before the Advent of Islam

- Yannai

- Jews Under Islam

- Byzantine Jews After the Advent of Islam

- Qara'ites

- Saadia Gaon

- Saadia Gaon's Poem Telóf Tèlef

- Salmón ben Yeruḥám

- Hasdai ibn Shaprut

- Yoséf ibn Abiṭúr

- Andalusian Poetry

- Samuel haNagîd and Ibn Gabirol

- Christian-Jewish Polemics

- The Crusades and Maoz Tzur

- Rashi

- The Tosafists

- Yehuda haLevi

- Ritual Murder and Blood Libel

- The Ḥasidé Ashkenaz

- Toledot Yeshu

- Moses Maimonides, Philosopher

- Moses Maimonides, Rabbi, Leader, Physician

- Abraham Maimonides

- Maimonidean Controversies

- Host Desecration Libels

- The Barcelona Disputation

- Qabbala and the Zohar

- The Cairo Geniza

- The New Sephardi Identity

- David Reubeni and Shelomo Molkho

- Shabbatai Tzevi

- Da Costa and Spinoza

- Yiddish Texts

- Ḥasidism

- The Jewish Enlightenment

- Modern Jewish Thinkers

- Jewish Thought >

- Jewish Law >

- Scripture

-

Liturgy

- Daily Prayers

- Shabbat >

- Rosh Ḥodesh (New Moon)

- Shabbat Rosh Ḥodesh >

- Shabbat Zakhor

- Purim

- Passover/Pesach >

- Omer Counting

- Shabu'oth >

- Tish'a beAbh Evening Service

- The Month of Elul

- Rosh haShana (New Year) >

- Shabbat Teshubá

- Yom Kippur

- Sukkot (Festival of Booths) >

- Sheminí ʻAṣèreth

- Simḥàt Torah

- Ḥanukka >

- CHRISTIANITY

- ISLAM

- (DIS)COURSES

-

OTHER LANGUAGES

- UGANDA

- Contact